*Note: this piece falls chronologically after October’s “When It Comes Easy”.

I felt myself bristling as I passed the billboard of Mt. Rushmore at the state line. It only deepened as I kept driving. The first 350 miles, as I headed west from the Minnesota border, felt like nothing to me. It looked like nowhere.

I was on the interstate, which can do that to you. I’ve only ever seen eastern South Dakota at seventy miles an hour. As far as I know, it’s all grass, with occasional towering billboards for pioneer towns and ammunition shops, restaurants advertising their buffalo burgers. Tourist traps selling buffalo skulls. I know the names of the towns—Mitchell, Plankington, Kimball. I’ve probably been in some of them, but it was too long ago and I don’t remember.

I stopped above the Missouri River. I almost drove through the parking lot at the rest area and left again. It was full of RV’s and rental cars, with a stream of people walking out to the overlook. But I needed to stop. So I parked and ducked my head as I went into the rest rooms. I had been driving for five hours and my fingers were stiff from the wheel. I ran the tap and held my hands under the warm water until I felt halfway human again.

As I drove across the river into western South Dakota, I reached for my phone. I wanted to see if the time zone had changed. It hadn’t, which didn’t make sense to me. I restarted the phone, and the time was still the same. I set it down and picked it up again a few minutes later, checking again. I kept picking it up every five miles or so, assuming there was some lag in the satellites or something. I was pretty sure the time zone would have shifted at the river.

Finally, an hour and a half west, I saw the sign announcing that I had driven into Mountain time. I picked up my phone and, sure enough.

“Huh,” I said to nobody.

I could see the sod huts and little rickety buildings from a re-enactment 1880’s town by the side of the interstate. I passed the exit for Kadoka; then the big dinosaur at Wall Drug. Finally, after eight hours of driving, I was into the ticky-tacky hotels, the black fields of pavement outside the big box stores at the edges of Rapid City. To the north was Rushmore Mall, quietly decaying behind an empty parking lot.

I don’t know much about South Dakota. It’s just a big state that I have always passed through quickly on the way to or from my little pocket of home in the southwest corner, the Black Hills. I don’t know anything about the rest of it. The Hills are what I know. I think of that old worn-down arm of the Rocky Mountains, completely unlike the rest of the state, and I am torn into different selves. An alternating shiver of love and resentment. It’s the one place I can speak about.

“God’s country” is what adults always called the Black Hills when I was growing up. Now I know that everybody says that, wherever they live, or at least if that place is rural and underloved. But there was a coffee table book that came out when I was in school called “God’s Country” with photos of the Black Hills—the trees covered in snow, soft meadows lit under a single plane of sunlight. All my friends’ parents had a copy of “God’s Country”. It was in the local bookstores. If it’s still in print, it’s probably being sold at the tourist shops. I feel like I know enough about the book, although I never cracked the cover. I always hated that phrase, “God’s Country”.

I remember standing outside the city library when I was thirteen with a group of my friends. The street lights were flickering on at around 5pm. The sidewalks had been slushed over for months; they had melted a few times and refrozen full of mud. And the sky had been gray since morning, lighter and then darker. I was shivering in my winter coat, tucked under the arm of a boy who had just given me my first serious, and seriously gross, kiss. I was hiding my face from the light of the streetlamp, trying not to show my disappointment. I was open to the possibility that kissing was just gross by its nature and that boys were just like this—dull and odd-smelling, and annoyingly tall over me—but he was my boyfriend that week, and I was warmer with his big, dumb arm over me. Boyfriends were necessary in February in the Black Hills. There was nothing else to make life worth living. We were all huddled together outside the library, a few girls and a few boys. Trying to be clever. Trying to float over the vein of cruelty in the conversation, to hide any soft flesh where a pointed joke could sink in.

One of those girls would be pregnant by summer. The father was the boy with his arm over her. She and I went to different high schools, but later on I heard they moved into a trailer together in Hermosa with the baby. When I ran into her a few years later, after graduation, I asked her about the boyfriend and her face went dark. She was somewhere else for a second. “No,” she said. Something in her eyes closed over. “I don’t know how he is anymore. It’s been a long time.” We weren’t even twenty yet, but she wasn’t the only girl I knew who’d figured out what a long time meant by then.

I’m not saying it was worse than growing up anywhere else. All I mean is that the phrase “God’s Country” sounds like a joke to me when I hear it. It sounds like something you say and then spit on the ground.

I think of being thirteen because that was the year we had to decide—do you stay in the warm cocoon of childhood, with your dolls and make-believe, and be safe with the “good” ones? Some girls did. I don’t know where those safe girls went after school, but they weren’t standing outside the city library. That was the year I suddenly knew girls with track marks on their arms. Burn scars. Fresh razor scars over fading razor scars. When someone was absent from school for a week, it meant they were in Regional West, the psych ward. Sometimes it meant they were in Juvie. A lot of kids took a tumble that year, and some never recovered.

I survived in God’s Country by stitching myself a coat of indifference. When I was safe at home in the forest, I didn’t need it. I didn’t need it with my family, not with my teachers or with my books. But, when I was out in the cold world, there was just too much to feel. There were dozens of men passed out on the sidewalks in downtown Rapid City, so many that you learned to just walk over them. There was a boy who died in a motocross accident when we were fifteen; there was a boy who died in a car accident. There were parties—the chemical high that ran through a hundred dancing bodies, late at night in a barn outside Piedmont. There were parties where someone got drunk and fell off a cliff near Johnson Siding.

The sting of parties I was never invited to. The sting of invisibility. But I knew kids who got drunk in high school and then did nothing at all, forever. I knew girls who got pregnant and then you never saw them again—or else you ran into them at night, late, in the checkout aisle at the grocery store. Each year in high school, a different girl went around to talk to the classes as part of a twelve-step program to show us what meth had done to her. The school hung posters through the hallways with photos of sunken, blotchy faces and rotting teeth. The next year, there would be another girl, a month clean from her stint in rehab, who would interrupt the day’s Biology class, or Trigonometry, to recite a speech on what she’d learned.

Maybe it would have been the same wherever I was. Still, I can’t shake the indifference I learned here. I am carrying it with me. I try to stop myself grasping for it, but when something hurts, when I’m afraid, I want a thick bristle between me and the world. I don’t know how else to withstand the open country, not when the winds are screaming through. Not when you’re breathing the dirt from five states of parched fields.

Under my coat of indifference, I can hold a bored expression even while my pulse is racing. I can stop up my ears so I hear nothing; dull my skin and feel nothing. I reach for silence, and the widening moat of my silence protects me. It protected me when I lived here—especially with the bikers at the Sturgis motorcycle rally each summer. It protected me later, with the rich suits and manicured faces I met in New Haven after college; with boyfriends and with my husband. I have kept my bristle on hand through the years, to throw over myself quickly when I need to become unreachable. When I need to care less. To want nothing.

I am trying not to bristle at South Dakota, but I don’t know how to feel otherwise. I always wanted its love. I wanted to belong here, even as I was pushing it away. Driving west into the hills, I could feel myself rejecting all these towns again before they could reject me. I was preemptively annoyed with everything I saw. More signs along the highway for the casinos in Deadwood and the schlocky tourist traps around Keystone, more motorcycle leathers, more gun racks.

I don’t belong here.

How many thousands of times in my life have I felt that? I felt it here first.

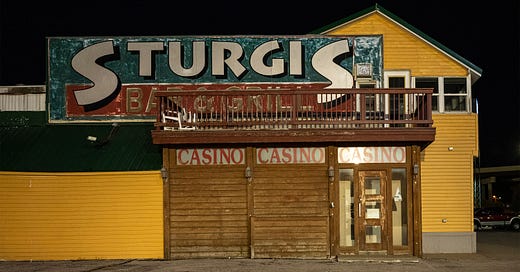

I arrived in Sturgis that night in a bad mood. I circled the town once, got gas and hit the McDonald’s drive-thru. Then I went to my hotel room and sat on the bed. I sipped my Diet Coke and stared out the window at the dark imprint of the hills behind I-90. I killed an hour that way, ruminating on all the ATVs stacked on trailer beds in the hotel parking lot and the canned sound of a local band down below me in the hotel bar. It felt like a big mistake to be here, especially on a Friday night, given that the bar downstairs seemed to be a big draw in town.

The hotel was new. I didn’t recognize it or the strip mall around it. When I checked in, I’d asked the clerk how long it had all been there. She just stared at me blankly. “I don’t know,” she said. “A little while.”

She rattled off the spiel for my stay—breakfast at seven, vending machines by the elevator. She pointed toward the Gaming Room and to the hotel bar.

“How long has there been gambling in Sturgis?” I asked her, frowning at the black tinted door to the Gaming Room.

“How long?” She repeated.

“Yeah, I grew up here. I don’t remember there being gambling in Meade County. Just in Deadwood.”

She shrugged. “As far as I know, there’s always been gambling here.” She called out to an older woman, who had wandered out of the office behind her. “Hasn’t there always been gambling in Sturgis?”

The woman stared at her. “Far as I know,” she confirmed.

I considered arguing with them. I remembered the vote in Lawrence County that legalized gambling in Deadwood. That vote had single-handedly gentrified a bleak, dying mining town into an even bleaker tourist shithole. The old buildings filled up with theme park casinos, geriatric buffet restaurants, and multiple shrines to Kevin Costner, of all people. I thought I would remember if Meade County had done the same thing. But what did I know? There’s a lot I don’t remember. And I’d been away too long to say anything about it. I took my room key silently. I suffered the elevator ride up to the second floor. Then I sat in my room and nursed my McDonald’s Diet Coke for an hour, trying to remind myself why I had wanted to come back here so badly.

I had wanted to know, after so many years, what it felt like. Now I knew, I told myself darkly. But I also knew I wasn’t in the mood to give the place a fair hearing. I’d driven for 700 miles that day, eating only granola bars and a late hamburger. It was dark outside. And I was in a bad place to be tired and hungry, too raw to my surroundings and spoiling for a fight. These hills are overwhelming to me, so many wounds and memories. This is where I felt everything for the first time, lost things, and shamed myself in every childlike, fumbling way. It was bound to bring up a big reaction after a decade away. I told myself to hold off on hating everything until the sun came up again.

If nothing else, I had one good reason to be here. I texted my sister to tell her I was at the hotel. She wrote back, and I gathered up my purse to head out to the Knuckle Bar. I had driven for twelve hours that day in order to arrive in time for my nephew’s twenty-first birthday, so I already knew there was one place in town where I would be welcome.

I slipped the hotel room key into my coat pocket. I found the back stairs to the first floor. Soon I was in the parking lot, then the driver’s seat. I pressed the ignition button. And I paused, wondering if my out-of-state car would get keyed if I parked it behind the bar. Oh well, I decided. There was nothing I could do about it now.

I drove out into the streets of Sturgis.

You should write for AAA, or maybe Town & Country. Because readers really do crave writing like this rather than the usual tepid and insipid consumer journalism that dominates legacy media. It's abundant in treacly clichés. This is a traveler's story wrapping around a meditation on time. It's kind of personal, too.

why do I think of picking at scabs after reading your wonderful piece, Tonya. I can relate so much to your words. I am good at burying feelings, learned at a very young age. but, sometimes you reluctantly pick and poke just to see what might be still lurking there.