The Lariat Motel

I saw the sign moving in the dark - the neon cowboy endlessly throwing his lasso - and I could not resist.

The first time I went through Fallon, Nevada, I stayed in a nondescript, modern motel. It was fine. It was the first night of my first real trip through the desert and any room was good enough. I stopped at the first place in town that had a “Vacancy” sign. On my way out of town, early the next morning, I don’t recall noticing the Lariat Motel, although I surely drove past it. Revelations would follow, one after another, in short order. That trip contained a lot of catharsis and it covered many miles of highway.

My second time through Fallon, I stayed at The Lariat. I saw the sign moving in the dark - the neon cowboy endlessly throwing his lasso - and I could not resist, so I turned into the parking lot. The sign pulled me in. The place was decades old, but immaculate. The office had a short hallway that ran into the living quarters and I could smell the motelier’s dinner. It smelled like fish. A very old, very thin man with incredibly bright blue eyes walked to the desk. He was quiet and efficient and went through the motions of checking me in. He was as professional as they come and he gave me a professional smile, but there was a twinkle in his eye.

I filled out my information on a small paper card. He stood behind the counter, which was a lesson in minimalism - a pen, a desk bell, and a small holder with business cards. On the wall to the left was a black and white aerial photo of the motel. It must have been taken from a low-flying plane and the place looked much more spartan and devoid of trees than it was now. He flipped a switch on some ancient control board behind him. I was self-conscious and sensed that he was evaluating me closely from behind his professional air of disinterest.

When I was done and had paid in cash, he gave me the key and told me where to go. He did not waste one word or motion. As I got to know him better over the years, he warmed up a bit. He must have spent over half his life or more doing this, and it felt as though I were in the presence of a master. A front desk virtuoso. I knew that his dinner and his life were waiting just a few steps through the hallway behind him, but I also knew that I was getting his full attention at that moment.

After we were done, I left to park the car and grab my single suitcase. There were signs on the concrete parking bumper blocks saying, “DO NOT BACK IN.” Nothing was left to chance at the Lariat.

I went to my room, which was incredibly large and clean. It was a perfect time capsule of early 1960s motel decor. There was shag-like carpeting, more chairs than I could use, and a comfy bed. The thermostat on the wall was a relic, but it functioned perfectly. A wagon wheel porthole window in the bathroom looked out on my parking spot. The only concession to the modern world was a 1980’s era television. This trip was before WIFI, the internet, or cellphones. The owner had thought of everything - the spaces outside were numbered according to the rooms, so nobody had to think about where to park.

A pool sat on a large wooden platform in the parking lot, but I never swam at the Lariat. In the bathroom, glassine covers wrapped the drinking glasses. They said “Sanitized for Your Protection.” I wondered whether they still made these or he simply had a huge stock from the 1970s.

When I left the following morning, I looked more closely at the motel sign. A small board at the bottom - the kind they use for specials, with changeable letters - said “God Bless America.” I drove away thinking about that.

I developed a fascination with the place. I would plan trips around whether or not I could stay in Fallon at the Lariat. My traveling partner in the 1990s, Peggy, also loved this place. We invented a personal mythology about the old man and lived for the short conversations we had with him every time we stayed there. We learned a little more each time.

He said he was Lithuanian. We knew he was old. Peggy would speculate out loud and one day she turned to me as we were driving across the salt flats west of town. She said, “Maybe he’s a vampire and he flies around the desert at night.” The next morning, we saw him furtively carry a bundle of laundry from a room in the predawn light.

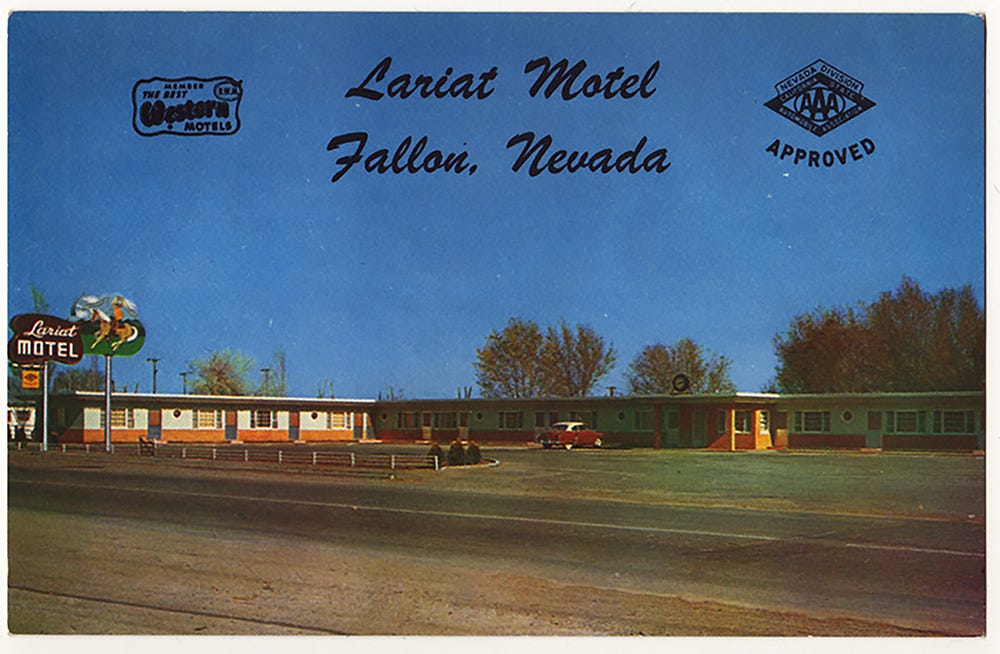

We got to know him in bits and pieces. His car was always out front - a gold Buick Electra 225 from the mid 1960s. He told us how, when he bought the place, the parking lot was gravel. There was a lawn and no pool. He pulled out an old postcard in a plastic cover. It was his only copy. It showed how the place looked when he bought it. I admired his car. “It runs perfect,” he said, although I never saw him actually driving it. This patch of desert was his whole life.

By 2001, the sign was peeling. I used to wish I could paint well enough to help him restore the thing. I dreamt that he would let me stay there for a week or two to fix up the sign. I asked him about it one day. He said it was 47 years old and had been custom made in Los Angeles and trucked there.

“In the 50s, Fallon had 3000 people and Reno had 40,000. There was no one who could make a sign like that. The closest place you could get it made was Los Angeles. I’m always fixing it. I have had it painted four or five times since I’ve had it. There are forty transformers in it.” He was proud of his sign. He knew what he had. “Today, you could not get a sign like that for twenty five thousand dollars.”

The last time I saw him must have been around 2003. He looked frail. When I checked out the next morning, I told him that I wanted to talk to him more about his life in Fallon. He looked at me with those blue eyes and said, “You’d better hurry. I’m not getting any younger.” He looked like he was 95. I drove off feeling sad.

The next time I went through Fallon, I made my customary pass by the Lariat to pay homage to my favorite motel of all time. When I got close, I found an empty dirt lot. I pulled into the parking lot next door to catch my breath. It felt like someone had punched me in the gut. I knew what this meant. I called Peggy from my cellphone.

She was living in Hawaii at this point, but she was awake and picked up the phone. “OH NO,” she said when I told her the old man was dead. She was devastated. I think we both had assumed the old man would live forever. Nobody lives forever. But why tear down the motel? I went into the curio shop across the street and asked the women there. They said, “He died and his son tore it down and put it up for sale.” There was little for me to say, but they looked sad as well.

I asked about the sign. They said the Fallon Chamber of Commerce had it. I drove back across the street for one more look and noticed one thing left on the ground after the demolition: the “God Bless America” sign. The next time I drove through Fallon, the lot had become a Maverik gas station. Sic transit gloria. All things must pass. God Bless America.

No more than a week after I finished writing my column about the Lariat, I was in Fallon again. For the first time since I saw it, I decided to visit the Maverik station where the Lariat had stood. Why not? I did not have to boycott it forever, even though I can hold grudges for a long time. Besides, I was now boycotting the other gas station, the one on the west side of town, so I needed to get over myself. I also needed gasoline.

I went in and bought donuts and some other stuff. A middle-aged woman stood at the register. I chatted with her for a while, then I paused and said, “This place used to be the Lariat Motel. Do you remember it?” She did not miss a beat. “Of course I remember the Lariat.”

I mentioned the old man to her and she remembered him as well. Then she paused a second and said, “You know, this place is haunted. He’s still here. When I go into the walk-in freezer, the lights never go off, even if I turn them off. They come right back on.” She paused again. “And sometimes, the heater gloves go flying across the room back there.” We stared at each other. “I’m not surprised,” I said. “This place was his whole life.” We each stood there for a second without saying anything.

I asked her about the sign and if she knew what had happened to it. She said that it was “propped up on the edge of town.” I asked for directions and she gave them to me, but they involved the local high school. I did not want to be the guy with out-of-state plates circling the local high school, but I decided to go anyway. As I was pumping gas into my tank, I looked at the place and realized that the walk-in freezer was in the section of the Maverik that stood where the old man’s apartment had been. I recalled how he would appear in the narrow hallway and float up to the front desk.

When I went looking for the sign, I could not find it. But I was determined, so I stopped into the Churchill County Museum, which I happened on by accident. Some kid was standing inside, holding a fluorescent fixture and waiting to talk with the woman behind the counter. The place was dead. It had strange and interesting memorabilia hanging on the walls.

The phone rang and the woman got into what seemed like an interminable call. I asked the kid if he knew where the Lariat sign was. He did, and gave me directions. I followed them and found myself at Oats Park, not far from the high school in Fallon.

Then I saw it. The town had mounted it nicely on two large poles. It was higher than it had stood in front of the motel, but they had repainted it and given it a home. That made me happy. I doubt the neon works, but I cannot be sure. Still, it’s good to know that it’s standing.

That being said, it felt strange and out of place. The paint job was crude and there was no context. I wonder what the old man would have thought? His heart would have been broken when they tore down the motel and I imagined he would not have been happy to see the sign way up high over this park.

I left the park and then left town. It felt a little less welcoming than before.

I intend to visit that haunted Maverik every time I hit Fallon. I’m going to stand around near the ice cream and whisper to the old man and see what he has to say.

Photos by Paul Vlachos.

This piece first appeared in EXIT CULTURE: WORDS AND PHOTOS FROM THE OPEN ROAD. You can purchase the book on Amazon HERE.

You can contribute any amount to Juke using these Venmo and Paypal links:

Paul Vlachos is a writer, photographer and filmmaker. He was born in New York City, where he currently lives. He is the author of “The Space Age Now,” released in 2020, “Breaking Gravity,” in 2021, and the just-released “Exit Culture.”

oh I just love this story! If I ever find myself near Fallon, NV I will stop by the Maverick and pay my respects to the past. and hopefully feel your gentleman's presence.

Impossible to love this more than I do...it has me wrapped in intrigue & saudade, though I have never met this wonderful gentleman nor seen the Lariat sign in person. It's an elegant word portrait of life well & quietly lived - & the sad inevitability of loss. Just beautiful.