Note: this piece is a continuation of “Books and Coffee: In Town”, published last November.

I drop dad off at the house and ask him if I can borrow his truck. He says sure. He asks where I am going, and I tell him the truth, which is that I don’t know. There is another bookstore downtown, one Dad isn’t aware of, and it’s a bookstore I like to peruse alone, or at least I have in the past. It’s one of those bookstores when we open the door there is an immediate scent of old books.

Dad reminds me that my mother will be home soon. When I was a boy, Dad would tell me that my mother would be home soon and that we needed to pick up the house. The house is a mess. It’s those expressions we keep from our childhood. We need to pick up the house. Let me get dinner started. The house is a mess. Or a favorite expression from my grandmother, my mother’s mother, who said, as some testament of her independence, That’s ya’ll. If, for instance, Dad and I had decided to drive two hundred miles to fish a river in a winter storm, my grandmother would shake her head and say, That’s y’all. Or if my sister thought to rent an over-priced, moldy apartment in a low rent district of a university town and do so with four other young women, well, that’s ya’ll. I heard the expression so often in my childhood that I sometimes sing the words with a favorite jazz tune:

I can only give you love that lasts forever

And a promise to be near each time you call,

And the only heart I own

For you and you alone,

That’s ya’ll, that’s ya’ll.

My grandmother’s sister, Aunt Velda, started using the expression, It’s a big world. In conversations when people might say, It’s a small world, Aunt Velda would say, It’s a big world. Velda could report on a family picnic when, while in town, she had run into her old friend, call her Nelda, shopping at Wal-Mart because her son, call him Paul, was coming home for the weekend. Paul had been a friend of Velda’s son, call him Larry. Larry and Paul had attended the same heavy equipment operating school after high school. Now, put everything together: a family gathering, a chance meeting in Wal-Mart with a lifelong friend, a lifelong friend whose son had attended the same school as your son. These layers of connection are what most of us would identify as “a small world.” Unless you were my Aunt Velda, for whom the world had become big.

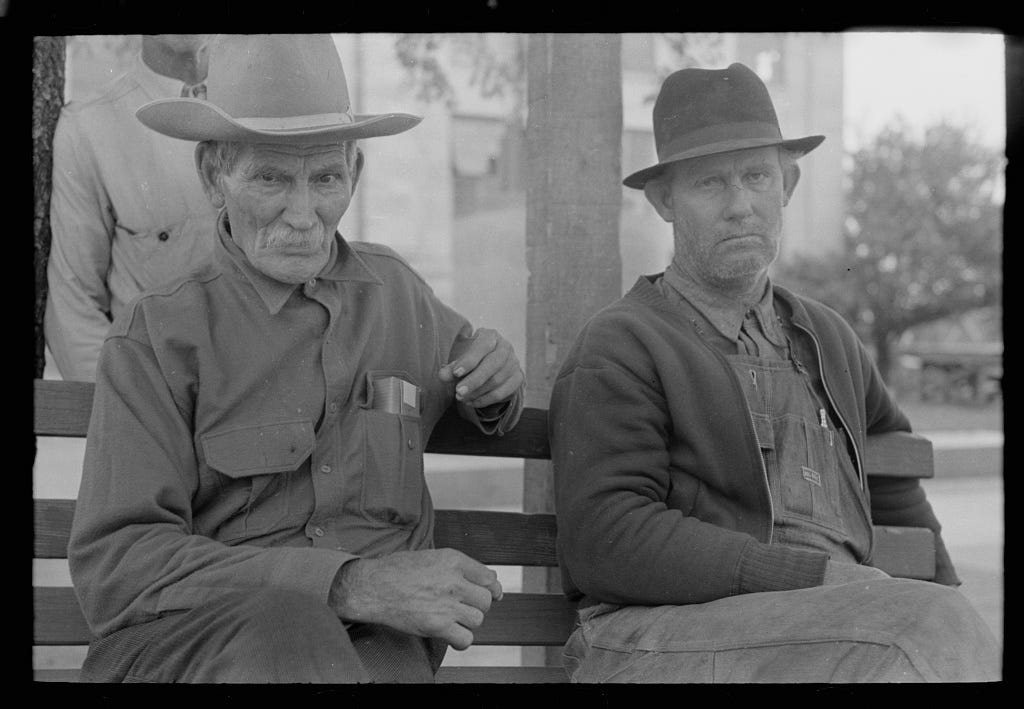

I drove away from my parents’ cul-de-sac thinking about Aunt Velda. No one specific memory came to mind. What I saw was Velda sitting at the bar table that divided my grandmother’s kitchen from her dining room. It was here that Velda and my grandmother, along with my grandfather, Doug, and Velda’s husband, Karl, liked to play Crazy Eights. They could play cards for hours. Sometimes it was the men against the women, sometimes it was Karl and my grandmother versus Velda and my grandfather. They took short breaks, during which my grandmother would stand up and stretch and start another pot of coffee and maybe, if the others were interested, serve plates of dessert, which, in my grandmother’s house, usually meant chocolate pie or coconut cream pie. I still hear their voices. I hear my grandmother saying shiiiiiitttt, whenever a play caught her by surprise. I hear my grandfather insisting that someone had put the big dog on the little one, if a hand had been trumped. What I do not hear and what I was too young or too ignorant to listen for were their stories. These were people who had grown up poor. They had lived in sawmill towns and lived off small farms. From looking at their photographs, I can enter their ratty yards where the men squatted to talk and where they shared beers and smoked cigarettes. They went barefoot through their childhoods. They picked cotton and timbered trees and repaired their own cars. They grew up and took their way out of the country and into a town along the Texas Gulf Coast where they could find better jobs, and they found them because of the war. They met each other and fell in love and started other lives. Over time, they prospered. They were never wealthy people, but they were comfortable with what they owned and what they had built and managed to keep. The brick homes of their middle years replaced the clapboard houses of their youth, thus fulfilling dreams. Although they had moved away from their friends and kin, they never abandoned the country of their childhood. Their old people and lands were never abandoned nor, in fact, was the land sold to anyone outside the family. They raked their yards and mowed their grass and wiped their kitchen sinks and went about their lives with passions and heartbreaks I will never know.

Driving toward downtown, I pass through neighborhoods where, here and there, cars are parked in yards and porches are crowded with the accumulation of spent hobbies and holidays. These are neighborhoods that my sister’s oldest daughter calls sketchy. She worries over crime, but she hasn’t seen enough of the world to appreciate that these are not sketchy neighborhoods or people. They are people for whom a pot of flowers or a new coat of paint could cost them a couple of meals or necessary medication. Are there criminal lives here, abusive lives, wounded lives, desperate lives, lives of need, wasteful spending, sloppiness, and laziness? Of course. But mostly the people in these neighborhoods do not have as much money as the people who live only one or two streets over. Is it their fault they are poor? I do not have an answer to that question, but I am sure that I cannot afford to live in the United States on the chance that I will get sick again, and I will get sick again.

It is noticeable that less than an hour has passed since Dad and I left downtown, and already the streets have softened under a new light. The sun whetted edges of hanging plants and flowers have diminished, as have the corners of buildings and benches. This is the sort of light and time of day when we might walk with our hands in our pockets. Most of the shops have closed or are closing at this hour, and we feel the borders of loneliness.

I park the truck in front of the bookstore, which, from the outside, is an unremarkable, cream brick building, with the windows blacked out by sheets of tinted paper. The name of the shop is painted on the door. Before going inside, I glance again at the street to witness this softening change in the hour. Across the street, at a place called Dream Cafe, a couple sits outside. They are in their twenties. They share a table. I appreciate that they came at an hour when they knew there would be fewer people here. The young man leans close to the young woman as he speaks. He contorts his head in such a way that he must look up to see her, a gesture which suggests a misunderstanding or perhaps a twist of regret. The woman sits straight in her chair, but this seems to be her usual posture. Her shoulders are square across her back. Her hands are folded onto her lap. Odds are we have been both or one of these two people. I am not sure why or for what reason, but I want to give them some forgiveness that they might refuse to give each other. I would tell them to go on loving each other, if they can, if it is possible. Surely there must be something between them to cherish, to love, something in the nearness of each other.

They may become, too, a recollection—this couple, this street. For years I have listened to people. I have watched them. I have kept notes about their stories and their whereabouts, all as an effort to remember them, believing that I might one day write about them. Yet I am no longer confident this is what I am doing or even if this is what I wish to do. I continue to listen. I continue to look. I sometimes make notes. But I am not saving them for their own sake any longer. It is possible in my saving them that I am saving myself. I have other scenes of other couples sitting across the street in my memory. They are a refuge. They are an occasional shelter from the casual dread to which so many of our lives are reduced. I have tried, though less and less as we have both aged, to speak with my father about these feelings of dread, but he is incapable of these conversations anymore. He does not lack compassion, but he can no longer clarify my struggles. I once asked my sister about this change in our father. We were on our way to visit our parents. She sucked in her breath, focused her eyes on the road, and straightened her mouth, not, I believe, out of tension but to prepare me for facts, for what in my family we call the hard truth. I think he gave it all away, she said. He spent most of his life taking everything in, every problem, every hurt, every death, every betrayal, every misstep. After all the comfort and compassion and advice and wisdom and prayers and concerns were given, there was nothing left. There is nothing left to give. How could there be?

Part of what I appreciate about this bookstore is that no one will ever ask me if they can help. Books are one of the few objects that I take pleasure in seeing clustered together. Rows and rows, piles and piles of books are a measure of joy. So much else that clusters gives me an impression of an infection. I am uncomfortable with clusters of things. I feel this even when watching skarven cluster together on the sea outside my home in the North. They do this when they are fishing. I have wondered, too, if they do this to keep warm. As a species, skarven, or cormorants in English, have been associated with bad luck and evil. In Paradise Lost, for example, Satan disguises himself as a cormorant eager to deceive Eve. Thinking of this, I find the nature section of the bookstore and search for a book about cormorants, but I am distracted by another book about ravens. This one is called, A Shadow Above: The Fall and Rise of the Raven. I say another because I have collected a few books about ravens and crows over the years, and this title is new to me. I am not looking for a particular book. Although maybe I will find a book for Dad. I could find another biography of Doc Holiday or maybe another biography of Shakespeare. Dad reads biographies about Shakespeare. I am not sure why. It doesn’t seem we have much knowledge about Shakespeare’s life, least of all his inner life.

There are good finds in the bookstore, more so than in the junkshop. I have stumbled on rare editions here—some the owner has been aware of and some she was not. Not many years ago it was much easier to find an undervalued book. Today most books that come into used bookstores are scanned for their relative value. The process begins well before the books hit the shelves. I have traveled to large, commercial book sales where table after table is covered with used books, and I have watched individuals prowl around with scanners ready in their hands. After the sale starts, these buyers will go to a table and scan titles with their machine. The buyers either keep whatever books they scan, by placing them into a shopping cart, or leave the books where they find them. They are scanning for price. Presumably the store owner, who may or may not be operating the scanner, has a price range in mind. The book’s condition, the edition, the dustcover, the author, a memorable inscription, none of this holds worth for most buyers, at least not outside of price. The value that a dustcover adds to a book is obscene. Although, there can be mistakes. A bored clerk still must place a book on a shelf. If the price hasn’t been marked and a clerk doesn’t wish to check the book’s estimated value, then she pencils in a price based on whether the edition is a hardback or a soft cover. This is how you find a signed first edition of High Windows crammed between dueling anthologies of love poems for a mere £4.

I stop in the regional section to scan a couple of shelves. I am sentimental about the books here. I want to think of them as I think of certain former lovers, for whom all my private questionings about what could have been, have been swept away and what remains is nearer to love. These books remind me of my formative years in the West. Volumes of Edward Abbey, David Lavender, John McPhee, and Wallace Stegner are tucked between books about the Colorado River, deserts, cowboys, fur trappers, Native Americans, ecosystems and ecology, and the fragility of so much. I can smell a cooling desert and sage after rain on these volumes. They are real to me, the worlds they keep, their scent. Yet they are also far away from my life. They will remain far away. Still the other day, while napping after a morning of work, I dreamed of horses. They stood in a stretch of desert between a line of tamarisk and the slope of a red mesa. It was for this, I believe, that I stopped.

I leave the bookshop without looking at the clerk. I am not confident about doing this.

Driving back to my parent’s house, the late afternoon has turned to dusk. All the lights through town and the neighborhoods have tempered the windows and porches into new stories. Dusk is the hour of a troubled beauty that we carry with us. We can linger with that beauty at the risk of being caught in the dark. Mom will be home. She will be starting dinner. That’s another of those expressions I recall. I’m starting dinner now. She will talk about her day, her many projects. There will be talk of her flowerbeds and what she is cooking for dinner tonight and the rest of the week, especially Sunday—she loves to talk about what she will cook on Sunday, and she always cooks the same meal, a pot roast, rice and gravy, and some boiled vegetable. She will talk about who called today, who she ran into at the store. She will speak of her friends as though I share in those friendships. She will make coffee. These are the habits my mother has cultivated to cultivate herself, to find her life within a life.

If you prefer to make a one-time donation, you can contribute any amount to Juke using these Venmo and Paypal links.

Damon Falke is the author of, among other works, The Scent of a Thousand Rains, Now at the Uncertain Hour, By Way of Passing, and Koppmoll (film). He lives in northern Norway.

love this series of essays, damon. you carry these stories and moments in time with such care.

"I leave the bookshop without looking at the clerk. I am not confident about doing this." Classic.