The Quality of Light: A Conversation

Before they leave to film in Greece, the Square Top Theatre team discuss their filmmaking process...

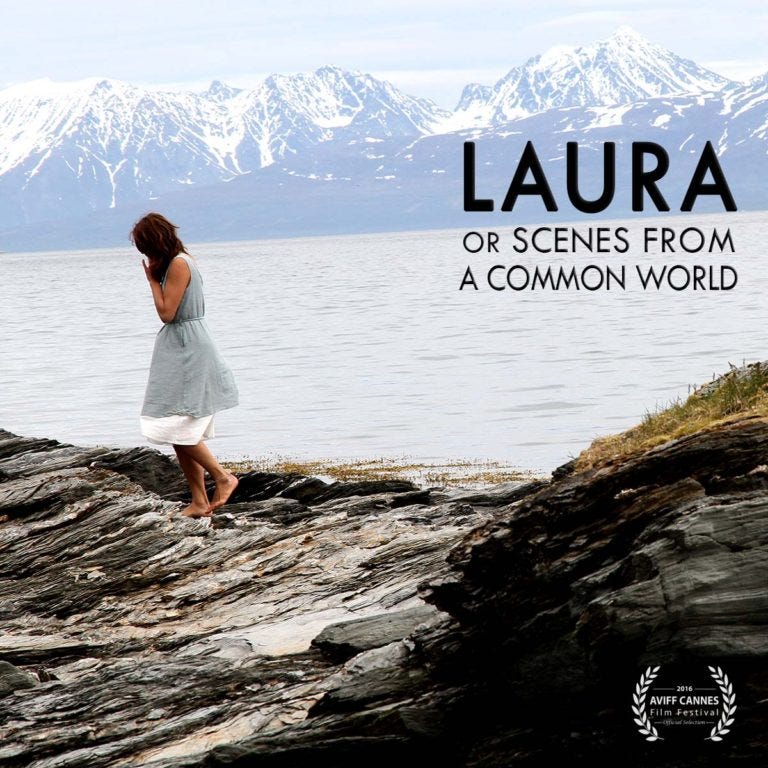

Note: Today’s post is an interview with the incredible creative team behind Square Top Theatre. These are names you’ll already recognize from the work we’ve shared on Juke. Damon, of course, is a regular contributor. And Charlie and Rebekah have been kind enough to let us screen a number of their films over the past couple years. If you’re like me, after watching a film like “Laura, or Scenes from a Common World,” you’re overcome by the desire to know how such a beautiful thing comes to be.

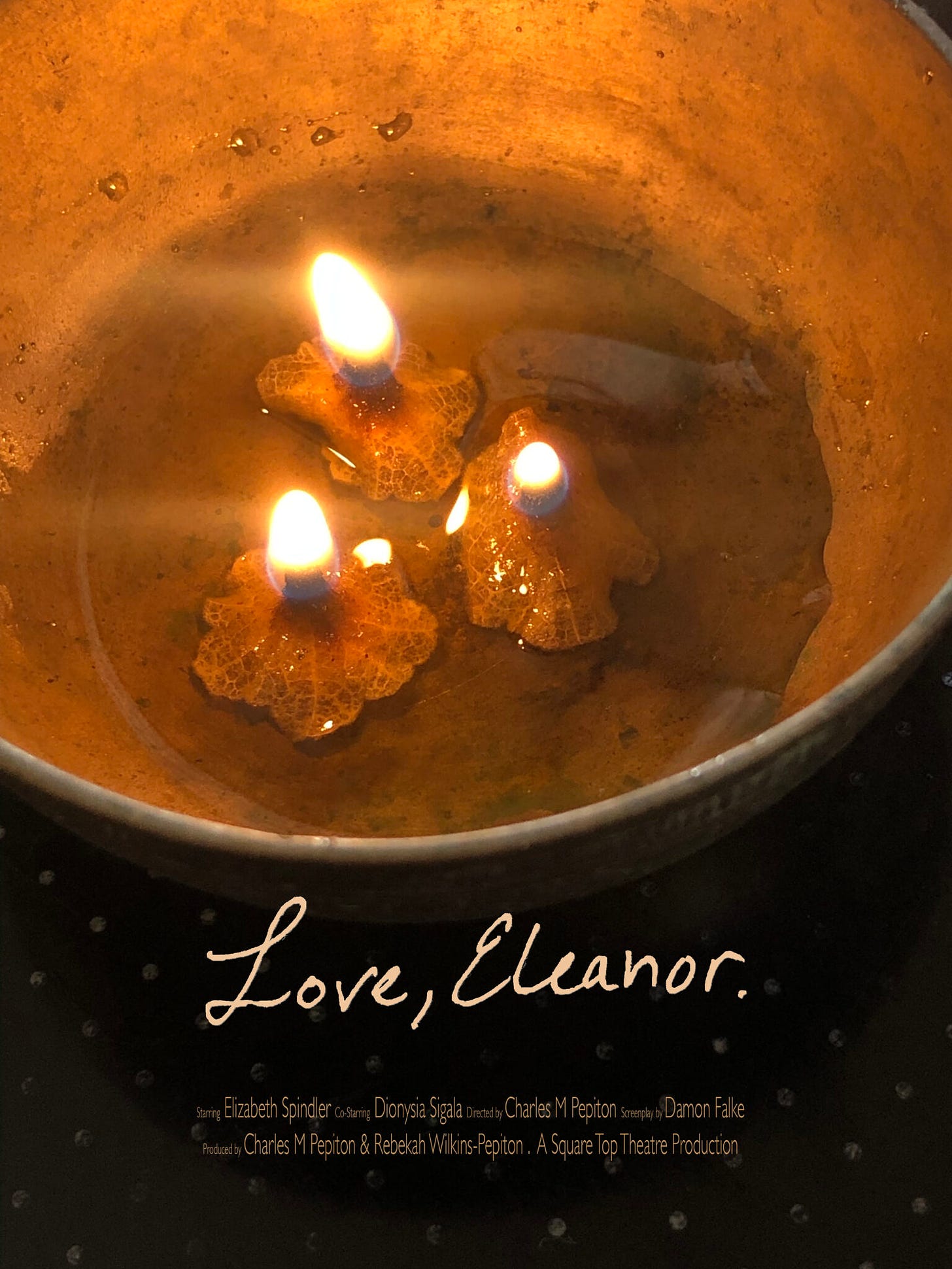

I wrote to Charlie after our recent screening, knowing the group will be flying to Greece this spring to work on a new film called “Love, Eleanor”. I was hoping he would give me (and ideally, everyone who reads Juke) some insight into Square Top’s creative process and into the development of the new film. Happily, he, Rebekah, and Damon agreed to answer whatever questions I had.

The interview ended up being a little longer than a normal post, so if your email cuts off before the end, just click the title of the piece to read the whole thing on our site. Thank you for reading! … TM

First, I’d love to get a sense of where each of you come from creatively. Can I get a quick background from each of you?

Charlie: I work as the Producing Artistic Director for Square Top Theatre and as Professor of Theatre and Robert K. and Ann J. Powers Chair of the Humanities at Gonzaga University. The easiest thing to say is, I work as a producer and director. That includes all the creative work of conceptualizing, casting, staging, and unifying, as well as managing the practicalities of project design, budgets, outreach, and coordinating between partners. And I teach those things. The theatre has always been my medium. I came to film and gallery installations much later.

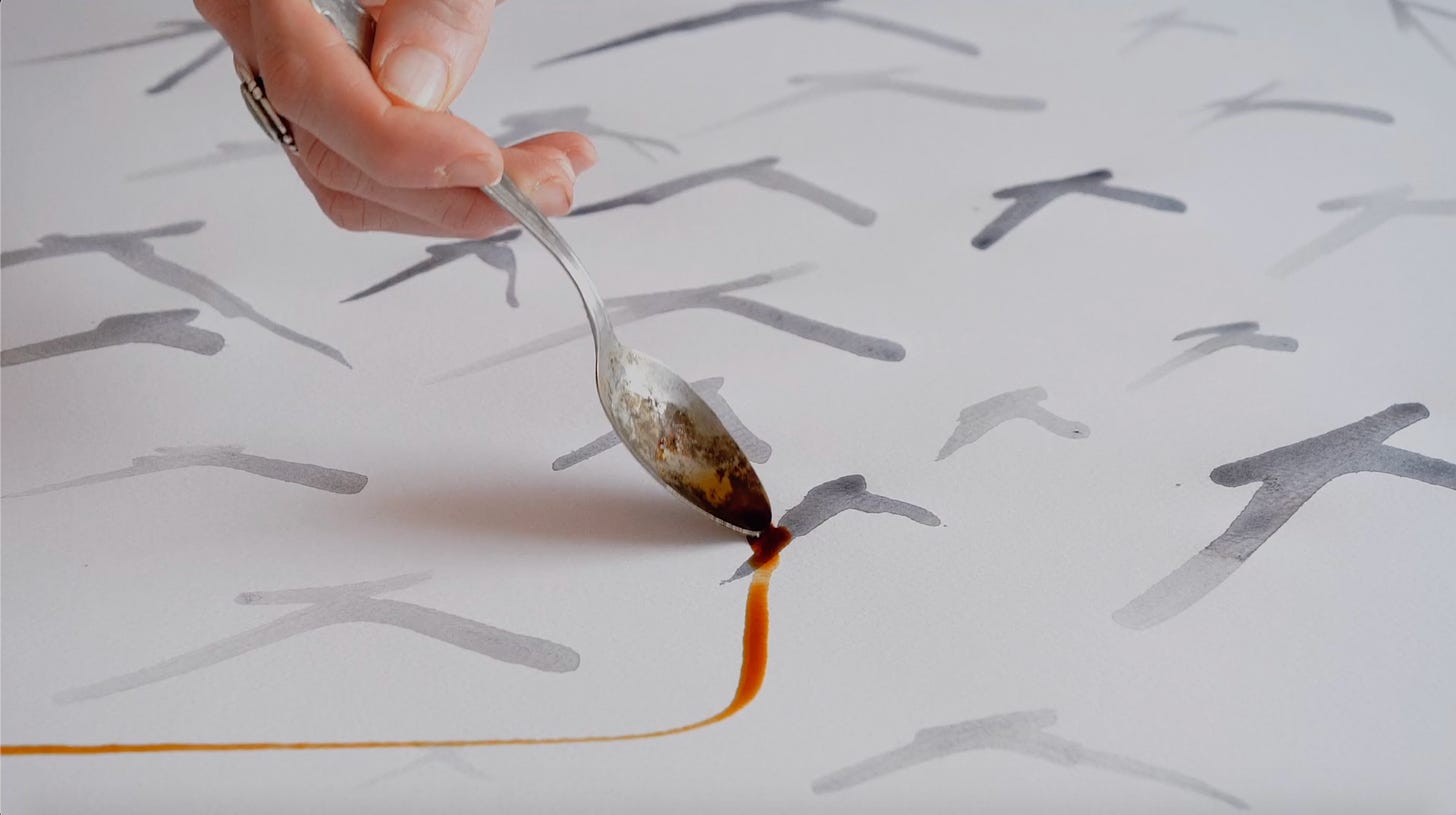

Rebekah: I entered the world of art through photography. My grandad was a photography enthusiast shooting aerial stills from the open air cockpit of airplanes. This passion passed down to me. I got my first serious camera at the end of high school and spent my college years with it as an extension of my hand. I worked for portrait photographers and commercial photographers during those years running darkrooms and shooting weddings, christenings, and fraternity parties. Along the same time, I was introduced to a variety of printmaking processes from relief carving to silkscreen. I began to combine the mediums to achieve what I now know to be “mixed process” prints. Since 2018, I’ve been working almost exclusively with inks made from foraged materials. I collect objects and botanicals then make ink using very old recipes. Working in this way allows me to be in collaboration with the materials of a place. There is nothing quick or particularly efficient about working this way. I find that it slows me down enough to give proper attention to where I am and recognize the specific resonance that occurs.

Damon: I come from East Texas, though I think of the Southwest generally as home.

Are you conscious of your creative influences? Which artists/filmmakers/etc brought you to where you are now?

Damon: I’m aware of who wrote the great works and who made the great pictures. The list doesn’t so much change as expand periodically. I like to seek out painters for influence. I love the work of Edward Hopper, Vilhelm Hammershøi, Andrew Wyeth, and other painters. I listen to jazz. Jazz is strangely visual for me, as a listening experience. When the right jazz number comes along at the right time, then I’m suddenly on any number of streets in the world, sitting at a café or waiting beside a window. I also listen to Classical music, though I don’t know Classical music as well as I know jazz. And lately I’ve been reading the Russians, but there is no imitating the Russians. When I say the Russians, I am talking about Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekov. A writer can learn from all strong writers, but there is no imitating them. T.S. Eliot had it right—it’s better to steal from them.

Rebekah: I love the rebellious and revolutionary spirit of the French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters. Van Gogh has been a hero since I was in high school. I love to read poetic prose from writers like Anne Michaels. I have learned about the potential of film to delight and perplex from Julian Schnabel and Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

Charlie: Certainly, I’m conscious of who my influences were as a younger artist, and those don’t go away. I know what tradition I came out of. I tell my students there’s a reason you like what you like. Lean into it. When you’re young, naturally, you imitate what draws you. What resonates with you becomes the point of departure. If you continue long enough, reflect about the questions and techniques that move you, and avoid undue compromise, you may uncover what it is you can do. Now, that’s not a formula for success, whatever that means, but it can clarify your voice.

I found my way into the theatre after a high school English teacher gave me a copy of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. I was astonished by its audacity and dark humor and how much it asks of an audience. You can’t be on the fence about the world Beckett creates. I like that. You either dive in fully and discover his work as enduring parables about the human condition, or you reject them as meaninglessness, “...where nothing happens twice.”

As a student, I was also fueled by what I read of modernist directors, especially Edward Gordon Craig, Peter Brook, and Jerzy Grotowski. They are the greats along a certain theatrical path. You know a Brook production when you see one. Here’s a director that worked in an enormous variety of genres from 1943 to 2022. Regardless of the source text or the play, from Shakespeare to epic Hindu poetry, Brook made the work his own, and he pushed for something greater than what could be accomplished in an individual show, something immediate, of its own unique time and place “where the invisible might be made visible”. His work also met a wide audience. It is exceedingly tough to accomplish both those things at once—experimentation and broad appeal, but he did it, over and over for nearly 80 years of active work.

There are others too, and surely, there are film directors I could name. Mostly, I’m influenced by artists who make distinct moves, who play with form, regardless of what the medium might be.

For instance, I saw a dance performance at St. Anne’s Church as part of the 2005 Cork Midsummer Festival in Ireland. I wish I could remember the company’s name, but the performance will never leave me. The stage for that show included three levels of an 18th century bell tower. Dancers played up and down the ropes activating the Bells of Shandon themselves, and then, I climbed to the very top level to discover still other dancers performing to the carillon in hidden courtyards and rooftops across the city. You could only see them from the highest lookout of the tower. It was a performance for a dozen audience members at a time.

More recently, I got to see Simon McBurney’s play/choreography/documentary piece Mnemonic from 1999. It was restaged in a 25th anniversary production at the Royal National Theatre in London this past summer. What an outstanding example of the invisible becoming visible, at least for the span of time within that theatre. I’m curious about art that is so difficult to classify, so audacious. I like an event, something that can’t be easily explained if you aren’t present for it.

I also travel obsessively. Travel is its own influence, an end and a means. I wander into galleries. I read.

I’m thrilled by shared research. As a company, Square Top often creates a reading list among the team as we enter a new project. We send each other titles and pdfs. This disparate collection is a central part of our creative process, part of finding ground for a new project. I just finished André Aciman’s essay collection Homo Irrealis, at Damon’s suggestion, and I am slowly working my way through Charles Taylor’s Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment. Both are a way into the next film project.

What brought you to this particular collaboration? How did you encounter each other?

Rebekah: Charlie and I met on the roof of a cafeteria on my 18th birthday. We were working in the mountains of Northern New Mexico. Our relationship has always been both a romantic and creative partnership. Years later we met Damon at a dinner party while we were all living in East Texas. It was clear from our first conversations that we had a similar way of encountering the world. It is rare to find people who continue to inspire you, encourage you and truly resonate with you.

Charlie: The story we tell is that we were co-wallflowers at a dinner party in east Texas. I remember that evening well. Beka and I met Damon and his wife Cassie, whom I taught with at the nearby university. Damon said that he was a writer, a poet. He mentioned obliquely that he was working on a play. I asked him what plays he’d seen and what he liked. At the time, he told me he had never seen a live production. I still don’t believe that, but the response left me curious about this playwright who had not seen a live play. Damon said he was working on a series of short poems. Beka was working on a set of photographs. They began to discuss how the two collections might set against one another. It felt like the first spark into a new project.

Not long after that, Damon invited me to go fishing. We stood together in a howling rainstorm for a day along the only cold-water trout stream anywhere in the region. He is a wonderful writer, but somehow, he might be an even better fisherman. I was glad for the guidance, being something of a hack on the water myself. On the ride back, Damon sang showtunes—full songs, mind you—for 90 minutes. I have a clear picture in my head of him white knuckling the overhead handle on the passenger side of my Subaru and swinging his elbow in time with “Send in the Clowns,” singing every word, pausing for dramatic effect. It’s a wonder our association didn’t end right there on the shoulder of the road in the rain. Somewhere along that ride, during a short pause between Sondheim and the Gershwins, he mentioned a script he was working on, and I said I’d like to read it. That was his play Canaan, which we produced as a staged reading a year or so later. I’d still love to find the right opportunity to stage it properly.

Damon: We met at a party none of us wanted to attend. Beka had a series of photographs that she believed needed poems. I had written and published a few poems. Beka took better photographs than I could write poems, but we shared a similar aesthetic. Charlie and I met more properly by going fly fishing together. We drove from East Texas to Oklahoma to fish. I fidgeted with everything in his car and sang bits of Broadway tunes for nearly the entire drive. I must have drove Charlie half-crazy, but at some point on that drive I told him that I thought I could write a pretty good play. He looked at me skeptically, though probably without knowing he did. After we fished, we drove back to East Texas, and I wrote a play. It turned out to be a pretty good play. It’s called Canaan. Maybe Charlie was surprised. I don’t know. But I knew I could write a play. I’ve been listening to stories all my life. I could hear the voices of those stories. You can’t write a play without hearing voices.

Can you describe your first project as a group? What lessons did that initial project teach you?

Damon: I’m pretty sure the first project was the book Beka and I did. The book is called Broken Cycles. It’s a series of photographs and poems. There was a lot we liked about that book, but all of us felt it was a little flimsy as an object. We didn’t know much about putting a book together, but we learned. Maybe the next project was Canaan. The play was performed as a staged reading in Pagosa Springs, Colorado. Over time and projects, we discovered how to work together. Beka has a sense of whatever world we desire to create or represent. She can see that world. Charlie is a tremendous project leader. He has a deep sense of story and what ideas a given story might comprehend. We still try to meet up every year to discuss where we are as a company, where we want to go. I enjoy these visits, too. We push for the next project, develop it, stretch it, tear it up sometimes. There’s a lot of energy spent. We’re exhausted by the end of a week.

Rebekah: In 2008, Damon and I published Broken Cycles: A Collaboration pairing my photography with his poetry. The project exists as a book and a gallery exhibition. Charlie served as editor/publisher. The project came together organically and was the beginning of what is now a greater than fifteen year friendship and collaboration. We learned how to control the means of production. This kind of independence has its advantages and disadvantages. It has allowed us to create work that defies easy categorization, but the “hollywood’ meal ticket has eluded us as of yet!

Charlie: Our first effort was bringing Damon and Beka’s book Broken Cycles into the world. It came out in October 2008 in soft cover from Shechem Press, which we also launched together. I’d love to see us reissue that book, at some point, in hardback.

Damon’s poems in that collection are spare and evocative, searching, and filled with far flung journeys. Beka’s photographs, all black and white, have a haunting quality that unites them: barns just before collapse, birds drifting over fields like smoke, ruined homesteads. I recall her describing, “altars of decline” as she compiled them. My favorite pairing, number XXVII in the series, features a photo of three windows standing square in their frames atop a crumbling adobe wall. The center frame improbably retains a three-panel section of glass. The individual bricks are perfectly straight, but the wall draws a fluid, wavelike curve under the sill line. The rows of bricks grow thinner but increasingly even as they get closer to the earth. In the background, and somewhat framed through the windows, piñons disappear into distant mesas that meet heavy clouds at the horizon. In the foreground, a crooked pinewood beam suggests something of a cruciform. Damon’s poem reads:

For three days he once passed through country where the sun rose like rain over dry fields

There’s a tension between his words and her images that calls for a response. They are not opposed, but at the same time, one does not illustrate the other. Never “one-to-one” —something we often say in our work together. In this pairing, “three days” corresponds with the three windows, but it is an imperfect rhyme. The cruciform bends that collision unwittingly toward spiritual matters and, perhaps, a remembrance of Christ’s three days in the tomb. But nothing is so obvious as all that. Maybe there is nothing so intentional at play. A viewer must navigate these tensions actively or miss what’s possible between them. It’s dynamic and open, but indeterminacy this precise cannot be haphazard either. In the collision between the words and images, there seems to be a surplus of meaning that a viewer can intuit without fully nailing down.

It’s a good example of what I’m drawn to as a director and something we’ve always tried to accomplish as a collective. Whenever possible each constituent part of a project should play an equal hand. The collision between elements composes the whole. Nothing is redundant; meaning is not fixed or presupposed. In that way, we trust an audience to move into the negative space to complete the creative act.

You asked about influences. The American director Anne Bogart writes, “It is not difficult to lock down meaning and manipulate response. What is trickier is to generate an event or a moment which will trigger many different possible meanings and associations.” I think we’re getting better at this. If you look at our first film, Laura, or Scenes from a Common World, this technique is all over the place. The elements collide in a complex way that can be alienating, though that isn’t the intention. I think film audiences aren’t used to having that much agency whereas readers of poetry expect it. In subsequent projects, I think we provide clearer on ramps and better interpretive guard rails. That probably reflects our own learning curve. Where we succeed, each viewer brings their own experiences and finds interpretations that are individually resonant. I think that’s why our conversations with audiences often exceed the runtime of the play or film screening itself.

You all seem very comfortable moving across creative genres—visual arts, poetry, plays, music and films. Was it always your intention to experiment across genres? Are there things you’ve done creatively that you wouldn’t do again? And when did you begin to focus more on filmmaking?

Rebekah: We started with the idea that we would pursue collaborative book projects and theatrical productions. We published some beautiful collaborations and produced a series of live theatrical productions that pushed beyond disciplinary borders. Now at the Uncertain Hour was performed and broadcast live via North Country Public Radio across their entire listening area in New York State. Film was the natural next medium for creative exploration. Coming full circle, we have produced gallery installations that allow audiences to more fully immerse themselves in the created world. The gallery work is particularly satisfying for me because viewers are often more vulnerable and open to “otherness” in those spaces and the likelihood of chance encounters increases.

Damon: It’s about choosing what form best represents a given work. A piece may work better as a film or play or a gallery installation or something we don’t know yet. Take your pick. The Scent of Thousand Rains is a poem, for example, but it became a stage performance. It works well for the stage. I had to adapt the poem for the performance, but that’s expected. Writers write, but we really re-write. As far as focus on film, I don’t know. Filmmaking is fun. There are a lot choices. There is also a lot we cannot control, and I appreciate those edges.

Charlie: I’ve always been interested in how different media come with differing audience expectations. It’s something to play with as a director. Working outside of a single genre or blending them broadens the scope of what’s possible and messes with assumptions. For example, theatre is primarily a literary artform. An audience will indulge heightened language from the stage more than on a screen. We want to see a play, but really, first and foremost, we hear a play. Film is more visual, perhaps exclusively so. You can overly write a film in a hurry, yet audiences will allow a bit more poetic phrasing in voiceovers. Music is inherently more experimental. An audience will accept greater musical risks and abstraction than in any other artform, but then, music can also be emotionally manipulative. Visual arts, particularly installations, provide opportunities for real immersion of an audience into the world of a project. You can play with all five senses. An audience walking through a gallery can be in the literal center of the aesthetic collisions. I’d love to play in galleries more often, but access can be difficult.

On a practical level, the idea of experimenting across genres also came as a solution to the problem of place and our access to one another and to an audience. Square Top began as a traditional repertory theatre company with aspirations for a residential company in southwest Colorado. We moved in that direction from 2006 to 2010, but after the economy dropped in 2008, a few founding members took other jobs, and our remaining team became increasingly far flung, we began working in artforms that were more portable and easier to accomplish with a smaller group. Southwest Colorado is well outside of a thriving art market for the kinds of things we like to make. We’re interested in creating new work exclusively. That’s a steep climb in this country, where you’re beholden to ticket sales, and in a region, where you’re reliant on seasonal traffic. Film, radio, and livestreaming developed for us as a way to work together in more remote places while reaching a much broader audience.

Your films have, so far, been set in Europe, either in Norway or in Greece. “Laura, or Scenes from a Common World” was in Norway. So was “Koppmoll” and “Without Them I am Lost.” Then “Climbing Eros” and also your newest project, “Love, Eleanor,” are set in Greece. Is there a reason you’re drawn to those two particular locations?

Damon: There are practical reasons for this, as well as aesthetic ones. I live in Norway, for instance. I have access to the stories and people here, which, I should mention, is something I do not take for granted. Greece is where we have traveled for a number of years. I can’t speak for Charlie and Beka, of course, but I think Greece is one of those places where we go to recover our lives. We re-ground. And it is Greece, after all. Telling stories in Greece comes with its own historical and cultural impetus.

Charlie: Travel for my family is more than a holiday endeavor. Anymore, I am happier on the road than I am at home. I feel more alive, more alert and open, when I am away. That’s not exactly something to strive for. It leads to shallow roots, and you have to be careful that travel doesn’t become tourism. A friend in Greece told me the problem on her island is that they used to get travelers; now, they get tourists. Tourism, as an industry, is as extractive and detrimental as coal mining. Travel can be far more empathetic, but that takes effort and time. A traveler can be devoted to listening and learning without removing or changing what is distinct about a place. At a pilgrimage site in New Mexico, a priest handed me a card that sharpens the idea. I carry it with me. It reads, “Live your life as a pilgrim not as a tourist.” Beka and I served in the U.S. Peace Corps in southwest China from 2010-2012. The relational part of travel and learning to partner with people across language and cultural barriers is part of basic training in Peace Corps. These film projects have been an opportunity to practice that as artists.

Damon and his family moved to Norway in 2013. We were fortunate to visit them that year and to see the southern part of the country. We have been back frequently now that they live in the far north. Norway has a pristine, untouched quality, that you don’t see most places. Locals carry wooden cups when they hike to drink from streams. As beautiful as our region is, I would never consider that in Washington State, and that reserve affects how you move through the world. I’m curious about how a particular environment shapes local culture. We are, as humans, coming unstuck from our reliance on place, but it’s an essential part of our animal makeup.

The films reflect these preoccupations with travel, pilgrimage, and what the art critic John Berger calls “address,” the way a landscape’s ‘character’ determines the imaginations of those born there. I’m moved by what I see in Norway and what I’ve come to understand about Greece. Beka and I have been fortunate to spend a lot of time in both places. They are very different societies, but both are formed by the quality of light and the way the natural elements still influence so many aspects of culture.

Rebekah: The reason for Norway is simple; it’s where Damon lives. It is also incredibly beautiful and fragile like so many wild places around the globe. The reason for Greece is a bit harder to sum up in a sentence. The place holds history and makes me feel alive and creative. We first visited upon request from friends in Athens. They told us that we would want to stay longer and longer each visit; two weeks is not nearly long enough. Those were prophetic words, we have made many return trips spending our summer months breathing Greek air allowing that vitality to wash over us. “Love, Eleanor” is set on an island that we know well and have come to love. This particular island has long been a haven for artists and musicians, not because of any luxury. Perhaps because it lacks artifice and is stuck in the 19th century due to their ban of motorized vehicles. Transportation is difficult, water is scarce, and churches are abundant. It is a place that immediately captured my imagination. I am excited to return to see early Spring on the island.

Each of the films displays a strong connection to the natural world. You have an eye, always, to what the grass is doing or how the light is moving across water. Can you speak in particular about your reaction to the landscape in those locations?

Charlie: Part of what we’re doing is asking a viewer to pause. The common things around us have far more significance than we usually catch. There are graces we miss all the time. I like looking for these flashes of contact where we might be drawn out of our habits, where the natural world trips us into a more contemplative mode.

Yesterday, I was walking across the Gonzaga campus on my way to teach a class. There’s a trail across the quad where the grass has been worn away by use. It cuts a sharp, centered, muddy diagonal across the green. Our maintenance staff must hate it. From a distance, I watched an undergrad stop to look. He was by himself but came to a sudden halt. When he continued, he began walking a slow serpentine path in and out of that desire line. It stopped me. I wondered about how many previous, individual steps formed that smear across the green and what it might say about freewill and habit. I thought about how playful it can be to make a different choice. I don’t think the student caught me watching, but for a moment on a grey Thursday afternoon, we were both delighted.

The light in Norway has its own quality. The same is true in Greece, though the quality is completely different. In the far north, the light becomes milky at certain times of day, but somehow, in all that richness, the light is clarified and clarifying. You can pick out individual trees and boulders on a distant coastline. It must have something to do with the angle at which it enters the atmosphere. The light just does strange things at nearly 70º N.

I still laugh about a time when we were shooting Laura. Wes Kline, who worked as director of photography, editor, and composer for that project, was setting up his camera for the scene where Laura goes to meet a ferry. We knew we only had one take, so we had to get it framed right the first time before the boat arrived or we’d have to wait two days for the next chance. Wes leans into check his focus and sighs, unhappy about something he sees. He hurries across the deck of the pier to reposition the camera nearly 180º. He sighs harder, rips off his hat, “Another fucking rainbow!” Only in northern Norway can you curse a rainbow and be fully justified for it. Only in northern Norway can rainbows show up on opposite horizons within seconds. It breaks some law of physics.

When we’re working in such immaculate environments, there’s a temptation to let all the National Geographic beauty fill the frame, but it doesn’t work. Strangely, that much nature, that much magnificence can be numbing on screen. Instead, you can go in close and find macro textures that are much more evocative in their specificity. I love the shot of the anthill in Without Them I Am Lost, for example. It’s a quick moment towards the beginning that comes as Damon has just spoken about people moving to the north. I like the shot for the texture, for its chaotic rhythm, but I also like how it bends the moment into metaphor. We make a similar choice in the opening moments of Koppmoll with Tore kneeling among the stones along the shore.

In Greece, I’m told by friends there that the light made the culture. The sun is so intense in Greece that the ancients figured out how to use stone to build the agora, the covered communal marketplace, just to get away from it. From that time forward, common people could congregate for longer periods of time outside their homes. That act of assembly created opportunities for extended discourse which led to a political system geared around rhetoric and argumentation. I’m no classicist, but apparently, you can draw a straight line from the intensity of the Greek sun to the birth of Western democracy. There are colors in Greece you won’t see anywhere else. Blue takes a different meaning. The cobalt of the Aegean has as much to do with the sun as it does with water quality, depth, the type of rock, atmospheric clarity, and low humidity. It all comes together in a relatively small region to create the “wine dark sea” described by Homer.

In Climbing Eros, color and the locally cast nature of it is a pivotal part of the pilgrimage shown the film, especially for Beka’s character. When we installed the gallery show for that project, I was struck by the unity of the palette between the film and Beka’s paintings. I suppose, it should have been obvious. She forged the ink from the island itself, but I found it striking to be in the gallery surrounded by so much of the island’s color reshaped in her work. I was stopped by how well it translated between the various media and how immersive it felt. It was like being back on the island.

Rebekah: My work has always wrestled with the troubled relationship between humans and the natural world. Lately, I am even more passionate about this. As our society dives headlong into AI, I am certain that the antidote lies in a renewed romance with wild places and unspoiled nature. There are no simple answers and no easy solutions. I think that people give attention to the things they care most about. I am idealistic enough to believe artists can help focus society’s gaze to the fragility of the natural world surrounding them.

Damon: We live here. It’s good to see where we live.

What are the drawbacks to filming abroad? And then, what are the benefits?

Charlie: I don’t know that I can point to any drawbacks, but there are challenges in working abroad we would not have locally. There are the obvious difficulties of language and cultural barriers, but for me, that’s an essential part of the creative process. When you realize normal assumptions cannot be made, even minor ones about scheduling or the availability of power, you take a little more time building relationships, making decisions, and devising backup solutions, just in case. There are fewer do overs available. That forces you to partner with who and what you find. Indeterminacy is an assertive creative partner, but working like that, you have to stay focused on the moment yet remain fully connected to the overarching spine of a project. It’s an essential tension that is sometimes difficult to balance. This is where directing gets to be the most intense. It’s fun, but it’s type-2 fun, so to speak. It requires an enormous amount of trust among the team and not just a little intestinal fortitude.

We were shooting the scene in Without Them I Am Lost where Damon finally makes it to the top of the mountain, and we had a moment of clarity on this. Here we were—Beka, Damon, and me—in a gathering rainstorm, in the Arctic, 30 feet up on a 60º slope, in heavy wet brush, struggling to move upwards with several thousand dollars’ worth of camera and microphone equipment—all sensitive to moisture—trying to get the shot while our 4-year-old was playing along the river below with Damon’s 13-year-old. In hindsight, there was a lot at risk. It would have been nice to have a full film crew, a craft service table with warm drinks waiting, and, maybe, someone to watch the kids while we’re working. But what else would we rather be doing? Where else could we get the intensity of that shot with such a small production footprint? Working abroad forces a generative dependency on what and who you find, and so far, I think the work is better for it. I’d love to have more funding to play with, of course, but working like we do allows for serendipitous moments that can get planned out of local and larger teams. As Werner Herzog says in his rules for filmmaking, “Get used to the bear behind you.”

Rebekah: The benefits absolutely outweigh any drawbacks. There is a thrill to working on the edge or even outside of your comfort zone. I tend to get complacent when anything gets too easy. I remember when we filmed the final “fishing sequence” in Without Them I Am Lost. We had to navigate bus schedules, hiking times up a canyon with no trails, and child care for our 4 year old son. We had one chance to climb the rocky bluff and get the shots before a late summer rain storm had its way with us. We filmed the final take as hail began to fall and managed to get everyone down to safety with enough blueberries for a cake. Working in this way makes me feel alive and that aliveness allows for hyper focus.

Damon: I don’t know of any drawbacks, except expenses. Films are expensive to make. Make a film anywhere you don’t live and it’s more expensive. Generally, making a film takes you someplace other than your day-to-day, which is part of the joy. And when you go abroad to make a film so much feels heightened. You look at an unknown city, an unknown landscape. You take flights at odd hours to faraway places. You meet people who sometimes give attention to lives and stories different from your own. All these things keep the fire warm.

What role has music played in the development of these films? Does that come last, or is it something you consider during the process of development and filming?

Damon: Music is a character. You want it sing like the other characters. As Charlie once told me, “Music is a strong spice,” and I believe that’s true. Music can be very manipulative in a film, as well. But the thing is all the parts—the writing, the acting, the cinematography, the editing, the music—need to work. When they don’t work, the film inevitably suffers.

Rebekah: Music is always central in development. The sound of the film with composed music and diegetic sound must be unified with the visual elements. We are essentially crafting a world that the viewer inhabits for the run of the film. Every project has unique demands for musical composition. For example, in Without Them I am Lost the composer was featured in the film playing a traditional Norwegian Hardanger fiddle and a standard violin. Her work to incorporate Norwegian folk songs into the score added beautiful texture and complexity to the film. In contrast, Climbing Eros was in post-production when we brought in the composer, music was critical to the film’s unity but it wasn’t necessary to have it composed during filming.

Charlie: Music is the heaviest hitter of them all. There’s a video I have seen that sets a 90’s television theme song against footage from The Soprano’s. Suddenly, Tony the mob boss is Tony from Who’s the Boss. It drives the point.

The music came in towards the end of the process for Laura and Koppmoll. As I remember, Wes composed the music for Laura as he was editing. Camilla Ammirati, who composed, arranged, and performed with Wes for our play Now at the Uncertain Hour composed the music for Koppmoll by improvising on her banjo with the roughcut. She wrote and performed the title song, and then we had it translated and performed by a couple of Norwegian singers.

Once we started working with Tana Bachman-Bland, however, music became more of its own character. She is a worldclass violinist, but she started composing during the development of our play The Scent of a Thousand Rains. Tana has a rare talent in that she can balance classical performance and its rigors with a willingness and ability to improvise, compose, and arrange. In Scent, her onstage character spoke only through music. She composed those musical responses, in part, from the cadence of Damon’s poetry and the actor Ryan Childers’s intonation of key lines. I didn’t know that was possible. She composed the score for Climbing Eros next. Tana worked with the rough cut to develop that music, and then Darrien Mack, our editor re-cut it all around her rhythms. Darrien is also a DJ and a performer, and his own musicality comes through in his edits.

When we began working on our feature-length doc Without Them I Am Lost, I knew going in that Tana would compose the score. We knew she would base her compositions around the Norwegian hardanger fiddle and its unique sound. If you’ve not seen the film, it won’t spoil things to know that Tana leads the winter sequences and plays a concert for the village at the community prayer house. However, it wasn’t until we were midway through filming in the summer of 2022 that we discovered how to put her onscreen as the catalyst to draw the community together. She traveled back with us to shoot the winter and concert sequences during the following November.

For Love, Eleanor, the process will be a somewhat different. We’re working with Michael Kropf, a composer and a colleague of mine at Gonzaga. Michael has an exquisite piece already composed that fits the landscape and themes of the film. He’s allowing us to use that piece and to rearrange it to fit the needs of the movie. Love, Eleanor is a cinematic answer to the questions raised onstage in The Scent of a Thousand Rains. The character of Eleanor is, in part, working to respond to the poet from Scent and his claims about the nature of love. Our hope is to screen the short film as the second act of a remounted stage production of Scent with a live, 14-piece orchestra playing the score live.

Do you see a relationship between traditional visual arts (like painting) and filmmaking? I particularly loved how you drew Rebekah’s inkmaking into “Climbing Eros”, and it made me consider how the same eye can be drawn upon for both a still painting and also a moving film. Is that something you think about?

Rebekah: I set out to compose paintings with every shot. In Climbing Eros the color palette was determined by the foraged pigments and the island where they were found. The colors and textures of the inks had a sense of unity with the place that only comes from using materials from that place. Vilhelm Hammershoi, a Danish painter, served as a major influence for the look of Without Them I Am Lost. We shot the film through a LUT derived from Hammershoi’s paintings. The elements and principles of design that guide my 2D art making provide a shared language for the creative team to approach choices of locations, shot angles, light, costumes, and production design.

Charlie: Yes, absolutely! Both Wes and Beka bring a visual artist’s sensibility to the camera. The visual arts also are a part of our shared research as we begin a project. For example, we studied the work of Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi as we began developing Without Them I Am Lost. There’s a muted elegance, a silvery light, a formal, almost severe geometry, and a great deal of empty space. All that fits the landscape and architecture of the far north. Beka even designed the LUT for that film—the “look-up table” that sets the mathematical parameters for color and density in digital video—around Hammershøi’s color palette. If you look at a series of his paintings and then watch Without Them, you can see the influence right away.

In Love, Eleanor, the lead character is an art historian focusing on Greek Orthodox iconography. Icons have a rigid vocabulary of visual forms and postures. The colors are more saturated. Eyes and hand gestures are prominent. The figures see you as you see them. Icons are reflective, in that they bounce light back toward the viewer and in that they are meant to promote introspection for the viewer. I imagine all of that will be important in how we tell Eleanor’s story.

I would like to hear more about your current project, “Love, Eleanor.” How did this project come to be?

Damon: Love, Eleanor has evolved from a piece I wrote for JUKE, a work of fiction called “Six Intimacies,” into a film script. As the writer, I desire to sit with the character. I desire to know her better. I desire to see her. The script was a challenge. It’s always a challenge to get the inner workings of a human being on screen. It’s easy to overwrite a film, as well, but this is where trust happens. I trust Charlie has a vision for the film and that his vision looks something like what I’ve written. I trust Beka can see Eleanor and see the world she inhabits. To write a good script demands conversations. There are a lot of conversations about intention, transitions, narrative, and a host of other things. For Love, Eleanor, after Charlie, Beka, and I had developed a fairly strong sense of the script, Charlie brought in the actor, Elizabeth Spindler. Elizabeth read the script. She had insights into the character and what she, as an actor and frankly as a human being, needed to feel more. I try not to be overly precious with scripts. Creative people bring their own insights to a project. It seems wise to listen to them.

Rebekah: Love, Eleanor offers a counterpoint to the stage production, The Scent of a Thousand Rains (2019). There is a mysterious relationship between a man and a woman at play in both projects. Where Scent focuses on the male perspective; Love, Eleanor brings us into the world of the woman. She spends her life studying Greek Icons and looking at these ancient objects facilitating divine worship. Looking and seeing is an act of love, and the film will take us into Eleanor’s struggle. We will shoot it on location in Greece at the beginning of April 2025.

Charlie: Damon and Beka can probably answer better where that character came from. The short version is that Eleanor sprang from the piece “Six Intimacies: a fiction”, which began as a collaboration between a series of Beka’s paintings and Damon’s short fiction. Our families were together on the island in Greece that summer before the piece was published in Juke. I think Damon wrote to where her paintings took his imagination.

The character of Eleanor commands the section that begins “She understood herself as being alone...” A lot of readers responded to that character who speaks of a man, a former lover, who “could not separate imagination from love.” The Him character in The Scent of a Thousand Rains tells us that love and imagination are the only things that might remain of us when we go. That was in answer to the question raised in our 2014 theatre production, Now at the Uncertain Hour: “What can we take hold of that will go on, that will not be lost?” Love, Eleanor will take issue with that question and his subsequent response.

Where are you now in the process of developing it? What are you anticipating in the next steps? Are there any new challenges that you haven’t encountered in the previous films?

Charlie: We’re in preproduction. Our team of five will travel together to Greece for active production in mid-April. Our plan is to shoot it sequentially over 8 days on the island. I’ve really enjoyed how much time we’re taking with the earlier phases for this project. It has allowed time for a lot of research and reflection. Damon was with us in Spokane for a residency at Gonzaga in October. We finalized the working script together then, and we’ve been tweaking it subtly as we go.

This will be our first true narrative film. Laura told a story, but anymore, I’ve come to see that first film as a cinematic poem more than as a traditional narrative film. This one is more linear fiction. Narrative films are more challenging. For one thing, viewers have more experience with them. Audiences know what good acting looks like. They know how a person speaks and what a natural reaction looks like. They feel it when something’s off even if they can’t say why.

I’m excited to be working with Elizabeth Spindler in the title role. Elizabeth is a talented actor and one of my former students from my first few years in Spokane. She lives and works in theatre in New York. Our team has been meeting periodically on Zoom to discuss the character and the world she inhabits as an art historian. Our table work has included, for Elizabeth, time to see the Byzantine exhibition at The Met. I wish I could have hopped over for that, but I’m doing my own research into that world: its imagery, traditions, and theology. The question is always how much research is necessary. At some point, you reach a limit as to how much can be overtly communicated to an audience, but there’s never an end to what might translate into intangible decisions. The more we know going in, the more we can be responsive to each moment when the camera is rolling.

Rebekah: Love, Eleanor is a narrative short film. The pre-production organizational demands of a work of fiction differs from a documentary film. Because we are creating the world that Eleanor inhabits, there are a thousand and one decisions to be made. The screenplay is complete and we have our cast. Now, we are developing shot lists and determining as many of the production design elements as possible. We will be on a tight shooting schedule in April making it critical to plan out as much as possible beforehand so that we can leave space for serendipity.

Damon: We’re finding the right notes, which, paradoxically, might be the wrong notes. As Miles Davis told Herbie Hancock, “Don’t play the butter notes.” Right now, given that we have a script, a crew, actors, a location, we’re on guard for the butter notes. And there are always challenges when filmmaking. We cannot predict what those challenges will be. However, most of them are not very sexy, which is contrary to what a lot of people think about the film world. How to get everyone to arrive more or less at the same time at Athens International Airport is a challenge. How much do we need to budget for mules is a challenge, which might be the sexier challenge, too.

Describe how you envision the completed film. Do you have a strong sense of what the finished project will look like, or do you prefer for it to develop throughout the filming?

Charlie: We’re firmly in the research phase, but I’m getting closer. By now, we have a good set of reference points for the look and feel, clips from other films that handle a technique or a similar character note particularly well. As I said earlier, we have the music already in mind for this one. That is such an influential guide for the emotional tone. I’m listening to Michael’s piece on repeat. I like to bring it up in a sound editor so I can watch the waveforms as it plays. It helps me to hear the song and see where its transitions and main themes are.

Beka and I are regularly talking through the scenes, working to clarify visual intentions for each scene, and how we might pursue a shot sequence to tell the story. I’m rarely a director, on stage or off, who predetermines many moments. That said, I had the opening shot of Climbing Eros in mind before we knew the full story. That image of our son, Wren, at 3 years old ascending the peak at sunset gave us our title and focus. I often like to have a clear idea of the opening and closing. It gives waypoints, but I don’t use storyboards. I wouldn’t be able to follow them in the moment anyway.

For Love, Eleanor, we absolutely know what we’re looking for in final moment, but it’s not a shot for shot idea. What’s important is what the final shot needs to convey. My plan is to clarify the approach for every scene and to know the function of each within the arc. From there, on the day, we can be more adaptive to what we find. Our plan is to do most of the filming at dawn and dusk. That will leave the broader daylight hours for rehearsals.

Damon: Like every new work that any artist worth his struggle requires, you hope it’s best thing you have ever done.

Rebekah: The visual language of Greek Orthodox icons will be quite influential when we begin filming. The deep rich tones of many of the icons will be in contrast to the intensity of the Greek sun. Light in Greece has been personified since ancient times as it has the power to enchant, mystify and overpower.

What is the most challenging part of the process for you? Is there any part you truly do not enjoy? And what part is most rewarding?

Rebekah: As a photographer, I get a total rush from filming especially when there is only one chance to get the take. When we shot the boat sequence in Climbing Eros, every aspect of that morning had to go right. We walked to the port an hour before sunrise to begin filming the arrival, walking portions and were on the boat in time to capture sunrise. There is no dock at the western end of the island, so the seas had to be perfectly calm for the boat to approach the rocks. That morning was the only calm morning of our two months on the island. We planned and sequenced all the filming locations, but there were still so many variables at play. I practiced those shots in my head for days before the filming. It’s like choreography or blocking a play.

Charlie: I have been told by a certain writer that I can be somewhat intense on set. We were joking about it this fall, and I said, “I don’t know what you mean. I always have fun on a project.” He replied, “Yes. It’s just that it isn’t always so clear to the rest of us.” Touché. I laughed out loud at that one. In my own defense, like I said, making films is type-2 fun. It’s like backcountry skiing. There are plenty of thrilling moments and graceful lines. There are also moments of real uncertainty and trembling. For that, you want a group with the right understanding of navigation and how to dig you out when you get buried.

The most rewarding thing for me is always working with the team, and working together over multiple projects. I love the grind of a long effort. It’s part of why I don’t like going into a project knowing too much about the intended outcomes. If I know from the outset how to fully pull something off, I’m not so interested. There are moments of such joy in the struggle to create.

I’m reminded of something I read about the construction of wellbeing. This was in Erling Kagge’s Walking. He quotes the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss who says that happiness has to do with balancing glow—his word for fervor/passion—with requisite discomfort. Wellbeing, he says, equals glow x 2 divided by the physical and cognitive pain necessary for an endeavor to be accomplished well. Without passion for something outside of yourself, no matter how much pain you might avoid, you can never reach true wellbeing. That makes a lot of sense to me. That’s a long way around to say making art is tough. There is pain in the offering, but that’s no reason to stop.

Lastly, I’d like to know if there’s something you’ve learned along the way that you’d like to pass on to others. Is there a piece of creative advice that’s been particularly useful for you?

Rebekah: Keep making things! Take joy in the act of creation that is a reward in and of itself. Know your audience and trust them to critically engage with your work. Allow yourself to ask big questions, even if they scare you and especially if they scare you a little. Leonardo Da Vinci used a highly experimental fresco process when he created his “Last Supper” in Milan, the painting is crumbling and defies restoration efforts. Yet, it is the single most influential painting of the biblical account of Jesus feeding his disciples before his crucifixion. We remember Da Vinci because he took risks, we remember him because he innovated. Today, we sometimes get fooled that perfection is the ultimate goal, but artists should instead be in the business of innovation.

Charlie: I can’t improve on Rilke, who says, if you know yourself to be artist, build your life in accordance with that necessity. “...your whole life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse.” That’s a tall order, particularly in the U.S., but it’s a line that often comes back to me. Make something. Make the next thing better. Do whatever you have to do to make the next thing.

Damon: Yes, there is. I take this from a movie I never tire of watching, which is Tender Mercies. When a group of young, struggling country musicians approach Mac Sledge, played by the extraordinary Robert Duval, they ask him for advice about making music. Mac shrugs and tells them, “Just sing like you mean it.” Sing it like you mean it. I don’t know if there’s been better advice for artists.

You can follow Square Top Theatre on their website and on Facebook and Instagram.

Charles M Pepiton is a film and theatre director, working as Producing Artistic Director at Square Top Theatre and Professor of Theatre & Dance and Robert K. and Ann J. Powers Chair of the Humanities at Gonzaga University. His work includes Without Them I Am Lost, Climbing Eros, and Koppmoll, among others. Read more at www.cpepiton.com and www.squaretoptheatre.org.

Rebekah Wilkins-Pepiton is a multi-disciplinary artist, art educator, and lover of the outdoors. She lives in Washington State. More about her work can be found on her website: www.bekawp.com

Damon Falke is the author of, among other works, The Scent of a Thousand Rains, Now at the Uncertain Hour, By Way of Passing, and Koppmoll (film). He lives in northern Norway.

Tonya Morton is, among other things, the publisher of Juke.

If you enjoyed this post, hit the ♡ to let us know.

If it gave you any thoughts, please leave a comment.

If you think others would enjoy it, hit re-stack or share:

If you’d like to read more:

And if you’d like to help create more Juke, upgrade to a paid subscription (same button above). Otherwise, you can always help with a one-time donation via Paypal or Venmo.

bravo guys, a wonderful sharing of insights and feelings. knowing all of you, it was great to be a able to "peak behind the curtain" to see your individual expressions of what the creative process is, and means, for each of you. can't wait for "Love, Eleanor!"

So many wonderful nuggets in here. I'd like to comment more, but I think would have too many individual moments to talk about. So, just briefly: "Broken Cycles" -- I love that book. It still holds up as hauntingly beautiful after all these years.