The Walking Cure

I gave myself the instruction to see what’s around me, knowing I am perfectly capable of walking without seeing anything at all...

Bleecker Park has other names. Sometimes I call it Magnolia Park, for its proximity to the famous Magnolia bakery and for the white bakery boxes that overflow the trash cans on summer evenings. Sometimes it’s the Rat Park, for its most prolific residents, who race between the garbage bins and piles of decaying leaves, hoping for the tourists to drop crumbs from the bakery’s cupcakes and puddings. Neighborhood parents know the park for its playground. The delivery guys and taxi drivers, for its bathroom. The local dogs, for its sandy tree pits.

For me, it’s a place to pause as I leave my apartment. A place to listen. I walk and note deliberately each sound of Bleecker Park:

The swooshing of the park worker’s broom as he sweeps the yellow leaves into piles beneath the trees.

The confident, well-practiced patter of a vlogger at one of the benches, speaking toward her friend’s phone camera.

The roar of an angle grinder from the scaffolding across Hudson Street.

An occasional horn. More occasional than you’d expect. And somewhere, distantly, the wail of an ambulance headed to Northwell Health, the emergency clinic that replaced Saint Vincent’s hospital.

The squeals of children on the playground. The low chatter of their nannies.

The muffled conversation from a family of four sitting nearby, spoons in their mouths and cups of banana pudding in their laps.

The churning engine of a helicopter over the river, aiming for the 34th Street helipad.

And finally, the sound of an inner conversation, which began before I left the apartment. A disaffected voice still tugging at my sleeve.

There are hours when the world tastes like chalk. I don’t quite know how to explain. The feeling isn’t sorrow. It isn’t anger. I am not a particularly dramatic person, and even my worst moods are quiet. When I am unhappy, it’s more like restlessness, or the continual inability to get comfortable. Most days I am full of opinions and strong desires, but in the hold of this blah-ness, I don’t crave anything. Really, it’s more than that. It’s that I stop believing anything is worth craving.

Food just seems like food, something to put in your mouth. The news looks like yesterday’s headlines. Even music—I don’t believe it will take me anywhere. By far, the worst is to be inside with my thoughts, because my thoughts are as boring as greeting cards. But any diversion sounds like a disappointment. So why reach? Why do anything at all? I have already read everything. I have already touched everything and I can’t find a spark. Are there mysteries anymore? All the blues are faded. All the reds. There is only chalk. A gray silt over the windows. A gray silt over the street. Stale crackers. A day like thin soup.

I think of John Berryman’s mother, who told him (repeatedly)

“Ever to confess you're bored

means you have no

Inner Resources.”

I agree with her. On a day like today, I have none.

Each time I fall into this mood, my mind believes it will last forever. Which is wrong. Which has always been wrong. Consider a mood—even if you try to place your finger on it, it shies away. It’s too weak to last even the length of an essay. I read somewhere that any given feeling lasts about 90 seconds, which seems much too short. But forever is obviously too long. What is closer? Maybe a half hour? If I pick up the right tools, then I can begin to remember the way out.

What happened today? I woke up alright, but fell shortly into blahness. I did my usual things. Went out with the dog. Ate breakfast. Then I read my emails, read the news (the likely culprit, right there.) I emerged after an hour or so, realizing I was deep in the chalk, and I prescribed myself a walk.

I can’t just go out. I need to pay attention. People. Colors. Trees. I gave myself the instruction to leave the apartment and see what’s around me, knowing I am perfectly capable of walking an hour without seeing anything at all. I can burrow myself so deeply into my own thoughts, pull the mood over myself like a blanket, and walk down the sidewalk with the thick fog of it around me. In order to escape myself, I must enforce rules on the sullen voice in my head. Stop chattering, voice. Stop. Be silent for a minute. Look. No, with your eyes.

Leaving Bleecker Park, I pass two large Saint Bernard dogs who have flopped out across the stones. They are napping. One glances up at me, his tongue lolled to the side. On the bench is their owner or maybe a young dog-walker. She is bent over her phone. She wears a red ribbon in a bow around her ponytail. The ribbon is extraordinarily red. The dog’s tongue is extraordinarily pink. His big curious eye stares up at me as I walk past.

I realize I probably should have left my phone at home (when did I last do that?) as I feel a buzz from the device on my wrist. I have a new notification. An email from our city council member to remind me that next week is the neighborhood paper shredding event. Somehow, this perks me up a little. The paper shredding event. I have never gone to the neighborhood paper shredding—I have my own paper shredder, and if I didn’t, I would just shred the few credit card offers and irrelevant but personal papers with my hands, tearing them in long slender strips and then ripping those strips into smaller pieces. I can imagine myself shredding big piles of paper this way, slowly, over the course of hours, and it sounds extremely satisfying. But I get this email once a year and, once a year, I imagine the neighbors gathering in some big room nearby to shred their papers in concert, standing with each other in long lines, holding stuffed Ikea bags and Fresh Direct bags of the years’ unsolicited mail and discarded forms. I imagine shifting dunes of white paper confetti across concrete floors. I imagine love letters and ten-year old tax forms mulching together under the feet of all my neighbors.

Wouldn’t the rats from the rat park love to come to the neighborhood paper shredding? I imagine their wintry nests lined with fluffy white paper straw. Nestling in to sleep in warm, white little rat beds speckled with black type. I smile down at the Saint Bernard, thinking of this.

I need milk, which is no reason to go to Sixth Avenue, but I’m going there anyway. And as I walk along Christopher Street, I ask myself whether or not I might be living inside a play. Everyone looks so intentional. The two women laughing together in flowered dresses and metallic tennis shoes. The camera man pulling cables from the NY1 news truck. Even this grim-faced man passing now, with his stained white tee shirt tucked primly into his sweatpants. Aren’t the sweatpants too well-matched to the yellowing white shirt? And why does he look like he’s hard at work right now, wearing his firmest expression, when there’s no way he’s working in that outfit? A small, hard-hatted construction worker steps off the sidewalk to let the man in sweatpants pass.

In Bigelow pharmacy, the hairbrushes are extravagantly expensive. The bath oils are German. I consider the shampoos, the impossible British toothpaste, then sigh and leave.

Next, inside Citarella, the grocery store, I stand for a long time at the soup display. Lentil is reliable, but today it seems boring. Escarole and White Bean is more special, but it’s often oversalted. Bouillabaisse is far too luxurious for this mood. Finally, I pick up a small tub of Pasta Fagioli and put it in my basket. This store, it makes no sense. The bananas are too expensive, but somehow raspberries are cheap. I put the special yogurt in my basket. The special crackers. What did I need? That’s right. Milk.

A small shop called the Locavore Store has opened on Sixth Avenue, next door to Citarella. It sells local things, a mix of wooden spoons, candles, pantry supplies and other little treats, all produced within a hundred miles of the city. I like the shop. I like its smallness. It’s probably only thirty or forty feet deep, with a counter at the back. I walk from the front door to the rear display, deliberately lingering to touch the cloth napkins and smell each of the candles.

“Hi,” says the store clerk, looking up from the iPad on the counter. She smiles at me.

“Hi,” I reply hoarsely. Where is my voice? Still under the chalk. I try to smile and somehow manage to fail at it. My lip catches on a tooth—am I smiling or do I look like an idiot? I glance away.

A tight turn into the other aisle and I find a bottle of essential oils from Brooklyn called “A-OK.” Apparently, it’s supposed to brighten your mood. I uncap the test bottle and lift the stopper. It smells grassy and a little fruity too. I breathe in, hoping it will do its work.

Maybe I should buy it? The little bottle is $30. I sniff again and ask myself, in a week will this still interest me? My tastes are so fickle. I have ten other little bottles of fragrance at home, all nearly full. They each smelled like one thing in the store, but then something else at home. Already, with a second sniff, I’m unsure.

I set down the bottle, having disappointed myself in advance. Somehow I’m a little less a-okay than I was before.

No. No more smelling things.

Back on the sidewalk, the two women who have been walking ahead of me slow down outside an apartment building at 10th Street and Greenwich Avenue. I look up as two EMTs wheel out an old woman on a gurney in front of them. The conversation of the women abruptly switches topics.

“She looks okay,” one of them says quietly.

Behind me, someone else stops. I hear them report to someone else, “No, she’s alert. She seems alright.”

The old woman is strapped in, sitting up, facing forward in the gurney. Her eyes dart toward the young woman (her aide?) who walks beside the EMTs. The rest of us follow behind them, an unwitting parade. We trail at a respectful distance behind the two men as they angle her toward the rear end of the ambulance. For the first time all day, I realize I am not lost in thought. Now I am paying attention.

The wheels of the gurney roll off the curb onto the pavement, and as I slip past the little crowd of onlookers, I make a note: remember this. Remember this, when I’m sunk in worry, when I’m preoccupied with the future, when I’m drifting into grayness. If I’m not alive right now, at this moment, I never will be.

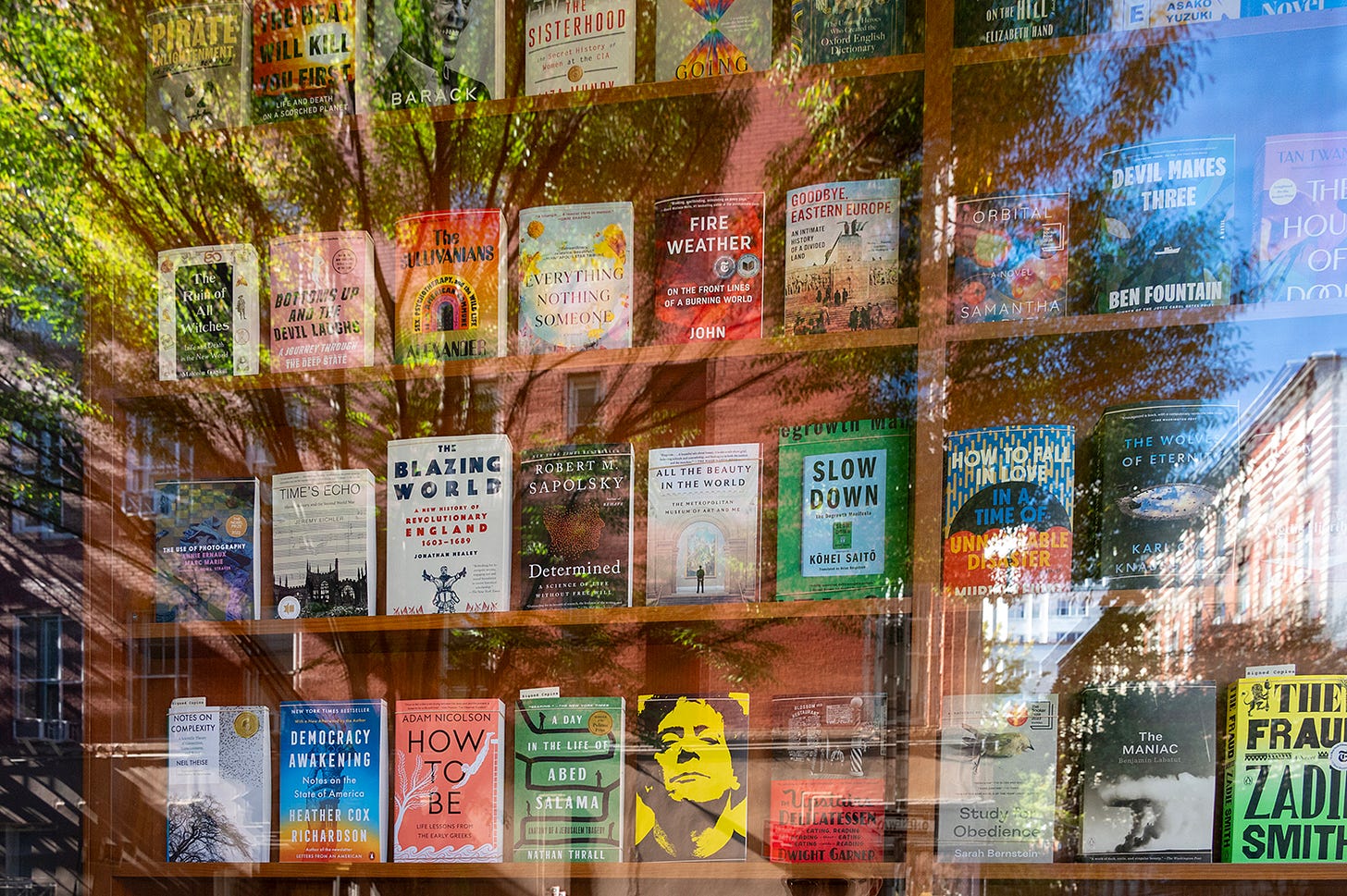

I stop on the next block and study the window at Three Lives and Company Bookstore. I console myself with the names of books I recognize. A few I’ve already read. One book, a baseball history, is written by a loose acquaintance. Others I’ve seen mentioned in reviews—the New Yorker or else the various bookish newsletters I’m subscribed to.

Still quieted by the thought of the old woman, who must now be speeding uptown in the ambulance, I adjust the long strap of the reusable grocery bag over my shoulder and go into the bookstore. First, I walk to the table of highlighted paperbacks. Hmm. I touch my finger to one, turn it over. Three Lives is famous in the city for the superior taste of its staff and the very particular curation of the books on its shelves. Any book laid out with special prominence is likely to be worth reading.

Behind the counter, a staff member is calling out to another: “Do we still have Speedboat on the shelf?”

Yes, I decide silently. Coming in was a good idea. Speedboat was one of the first books I read in the city. It was the New York Review of Books’ new edition. Renata Adler led me to Elizabeth Hardwick and then Eve Babitz—a journey that proved to be a closed loop, leading back to Joan Didion from whence I’d come. As I scan the stiff spines of the books around me, I think of all of those women in the store with me. Waiting on each shelf with their throats cleared, tongues sharpened, for the next pair of hands to pull them down and crack open the cover.

“Top shelf,” the other calls back. “There should be at least one copy.”

I pick up the new Garth Greenwell book—where did I see this reviewed? I can’t remember. I scan the back of the dust jacket, then open to the first page, first sentence. I read the rest of the first page, then I cut a fingernail at random into the center of the book and open again. Another paragraph. I sink into the words. Yes. This is good.

In the section of books on writing, I reach for Deborah Levy. The sight of August Blue in the window had been part of what led me inside in the first place. That book was a dream for me through the late summer. Now I see another from her on the subject of writing, and I repeat my ritual. Scan the back cover. Read the first page, then flip to another page at random. I smile as I recognize something in her words. (Yes. I could take this home.)

There’s a woman standing near me in Self-Help. To my other side, a man is bending down to scan the titles in Literary Essays. I glance at each of them, waiting to see if they open a book in the same order I do. There’s an art to approaching a book, and I always wonder if everyone does it differently. As I watch him, the man picks up a Rachel Cusk, flips it over, then he gets up. He catches the eye of the clerk standing a few feet away at the counter.

“This good?” He asks. He waves the book.

“One of my favorites,” the young woman replies.

Is that endorsement enough? I wonder. Did he even read the back cover? The man looks down at the book again, then tucks it under his arm as he walks across to Mysteries.

I look up to the shelf and run a finger across the books. Is that Geoff Dyer? I pull it down. It’s a book about his struggle to write a biography of DH Lawrence. First page, yes. Another page, yes. This is enough now. I have the promise of at least three books I still need to read. I put the Dyer book back onto the shelf with a sense of relief.

Crossing 7th Avenue, I pass a jazz club I’ve been meaning to visit for two years. A new restaurant with a trendy, forgettable name. Ahead, at the corner of Bleecker Street, a woman in a long tiered skirt is blossoming in the breeze. A man turns the corner too close and her skirt billows across his legs. He stops. She looks back and apologizes. In another story, I think, this would be the beginning of a romance, but the man just looks annoyed and keeps walking. I find myself staring at the skirt as I pass gingerly behind her. Little red flowers on dark leaves, woven with golden swirls.

Between the Oslo coffee shop and the Paquita tea shop a tall tree is shaking off its last leaves. As I pause to let a dog walker pass me, I look up in time to catch one wide leaf falling alone from the tree. The leaf cants sideways in the breeze as it falls, then it drifts the other way, spinning slowly, falling so perfectly. You’d think it was set to music.

As the leaf touches the sidewalk, I look up and catch the eye of a stranger. I can see from her face, the sudden light in her eyes, that she was watching it too.

I shift my grocery bag behind me so she can go into the tea shop. And, filled from fingertips to toes with a quiet happiness, I turn on Hudson Street to go home.

Tonya Morton is, among other things, the publisher of Juke.

If you enjoyed this post, hit the ♡ to let us know.

If it gave you any thoughts, please leave a comment.

If you think others would enjoy it, hit re-stack or share:

If you’d like to read more:

And if you’d like to help create more Juke, upgrade to a paid subscription (same button above). Otherwise, you can always help with a one-time donation via Paypal or Venmo.

I just walked through a neighborhood of Manhattan. Each person, each sound and sensation, lifted me out of my own funk. It's going to be a humdinger of a week, and this essay made it so much more endurable. Thank you, Tonya.

reading this was a lovely journey. I so relate to the state of "not feeling", to waking up to the day thinking, "why bother". I need to do this, just get out and observe and react and be a part of something, be a part of myself. watch a leaf fall. thanks,Tonya. your words always engage me.