What to Remember

I looked south and saw a plume of smoke. One of buildings had a huge, jagged hole.

For me, the 21st Century did not begin at the Baggott Inn, where I played three sets of music with a reggae band on the night of New Year's Eve, 1999, or Y2K, as we called it. It began on September 11th, 2001 and I took a photo the moment it happened. I was on my way to the second day of graduate school and walking across Greenwich Village to the NYU building on Broadway. I had just stopped at the southwest corner of 6th Avenue and Washington Place for a red light when I heard a loud siren and saw a New York City fire truck going full speed the wrong way down Sixth Avenue. The firemen inside were standing up and out of the windows, barely hanging onto the vehicle. I remember the looks on their faces.

They were all staring downtown and upwards as the truck weaved hard in and out of traffic. My head turned with the truck and I saw the twin towers of the World Trade Center. There was a plume of smoke, some flames, and one of buildings had a huge, jagged hole not far from the top. I carried my Nikon F3 at the time, loaded with some fast black and white film, and a 100mm lens - don't ask me why I had a medium telephoto on the camera that morning. It was shortly before 9am. I snapped a few photos. This was the first one.

Incredibly, I kept walking to class. I figured they would find a way to extinguish the fire. I went through Washington Square Park, where people were starting to gather and stare. Reality shifted a bit and an alternate, still-quiet narrative started in my brain, like a dream sequence. A homeless guy stood on a box and ranted about the end of the world. Mostly, though, people were just staring south. This was a terrible thing unfolding, and it was oversized, just as the Trade Center was oversized, but nobody knew just how bad it really was yet. It was still just an interruption in the day.

I got to school and class began. We all started to introduce ourselves, but everything felt distracted and fuzzy. Things fell apart not long after that, when a fellow student, who was also a reporter for Reuters, ran into the room. She screamed, “The second tower was just hit!” We all stood up without saying much and walked out into the common area, where a cathode ray TV set was on a tall stand. It showed a news feed. The first tower disintegrated live on television. That’s when I decided to head out. School was clearly over for the day. When I got down to the front door of the building, on Broadway, people covered in white dust were marching northwards in a grim stream up the middle of the street.

Oddly, I remember much of what happened that day. I went to Saint Marks Books, which was empty, and browsed the dictionary shelf. I told the counterperson I was surprised they were open. I stepped out and a group of people was gathered around a delivery truck with the radio on loud. Cellphones were not ubiquitous then and the existing ones were just for voice calls. I slowly walked home to my apartment, on Barrow Street, and discovered that my dialup internet was out, but that I was able dial into a school number. I phoned my dad to tell him I was okay and I got an email from a good friend in California, asking how I was. I made sure that my cat, Jayne, was okay, then I picked up my camera bag and headed out.

I started to walk down Hudson Street. Emergency vehicles were screaming downtown the wrong way. All uptown traffic had ceased. When I hit Houston Street, there was a roadblock, so I went west a block to Greenwich Street. They were not letting anybody go south, so I stood there with a large group of people. Lots of police were standing around, including some in civilian clothes who were holding rifles. A beverage truck came north on Greenwich, covered in dust, with fabric and plastic flying in the breeze from the compartments. It looked ghostly. The drivers were grim, wearing face masks, and the police waved them on. I am convinced they were transporting bodies and body parts. I wandered another two blocks to West Street, the highway by the river.

All we could do was watch the emergency vehicles roll downtown in the southbound lane. In the northbound lane, they were towing the remnants of vehicles out of there. Some were simply being dragged on the pavement at high speed, sparks flying. People watched and clapped for anybody who went by in either direction. I think it was the only way to cope with or make sense of something that made no sense.

Everybody seemed to wander down to West Street that day. We stood around, talked to each other, and gawked as the trucks went by. Some of us took photos. Others held up signs. I was moved that the signs said things like “PEACE” and “THANK YOU!” Other feelings would come later. The weather was beautiful that day. There was no Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or selfies, so we gathered in person. The air was filled with that awful smoke. People milled around, applauding and cheering every vehicle. Some people said nothing.

Later that evening, I walked a few blocks to Saint Vincent's Hospital, which had been dealing with the tragedies of New York City and the Village for over a hundred years. I don’t know what I was looking for, but we all figured they would bring the injured up there. They had set up a curbside triage station on 7th Avenue for the expected casualties, but none arrived. People either survived with few injuries or they were obliterated. The nurses and doctors eventually sat down on the curb and waited. Some guy was wandering around and he began to scream “LET THEM DIE.” I watched a scrum of cops run and tackle him. Most people were subdued. This guy had just snapped. Of course, we lost that hospital to luxury housing developers a few years later.

The next day, we were still trying to sort things out. Police arrived from across the country. The 6th Precinct, near me, had closed off 10th Street, their block. At the end of it was a police car from Independence, Ohio. These cops had gotten in their car and driven straight to New York to help out. This meant a lot to us. I printed a small American flag on my color printer and made a “thank you” note on the back, then left it on their windshield, courtesy of “The people of Greenwich Village.” In that first week or two, every time a fire truck went by, I stopped in my tracks and saluted them, holding it until they had passed. This did not feel strange to me.

Small posters and notices began to go up about missing people. They were everywhere and we soon realized these people would not be found. Strange stories began to circulate - somebody had survived the collapse by surfing the debris down the side of the building. This was outrageous and was clearly not true, but people wanted any story at all to make them feel better. Disasters breed fantastic stories. The truth was too awful. The air was filled with smoke and strange fumes. The “Missing” posters were now on every light pole and store window.

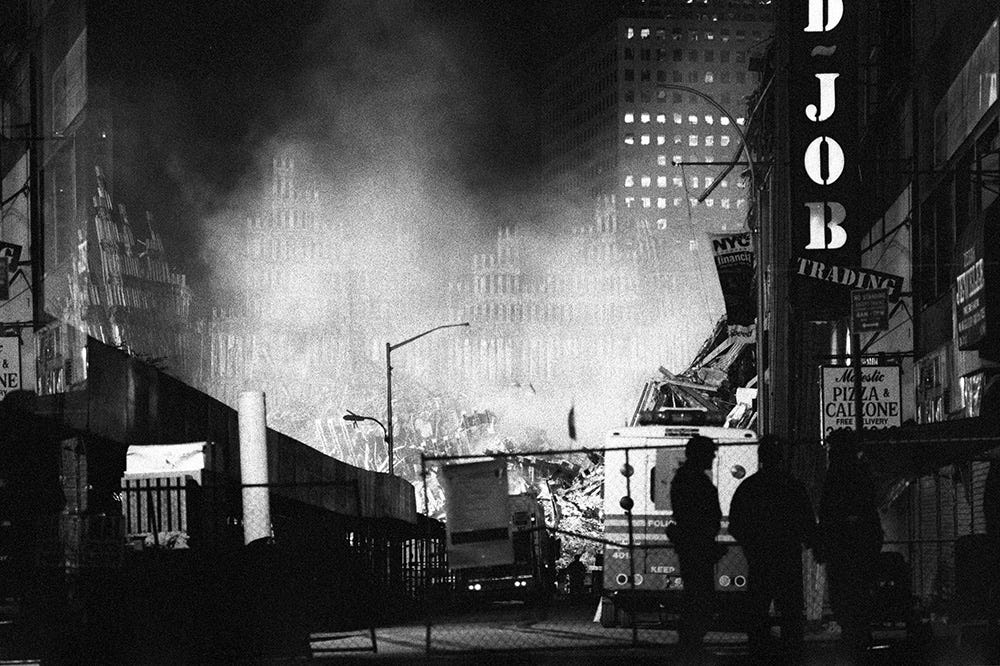

By the night of September 12th, a friend and I wanted to go downtown to see what was happening. Access was strictly controlled and we could not just ride there on our bikes. Eventually, we found a route over a footbridge on the FDR Drive to the East River Park bike path. No cops covered it. We rode down and then cut across the tip of the island. Lower Manhattan had already been declared a crime scene, and much of it was covered in white powder, the pulverized remains of the towers. There was broken glass, scraps of paper everywhere and the air was filled with dust. We tried to make our way to Ground Zero. We passed a row of destroyed cars near Park Row that had been towed from the wreckage. Some of these were barely recognizable.

At one point, we ran into a Sanitation Department crew. They were shoveling the white debris, which was inches deep, like snow, into cans and dumping it into their truck. They felt sorry for us and gave us some face masks. Until then, we had been breathing in the toxic cloud and I had put my shirt up over my mouth. We finally got close enough to see some of the rubble. I shot it with my 100mm lens. At that moment, some cops drove up and told us, “If you go one foot south of here, we’ll arrest you. Go home.” We complied. Those face masks turned gray in less than an hour.

People gathered in the parks in the following days. They gathered outside the firehouses, some of which had lost the majority of their crew. People lit candles and sang songs. Some of them made small ceramic tokens of remembrance at a pottery studio on Greenwich Avenue. They wired these to a cyclone fence next door. They needed to sort things out. The people who lived through it, across the country and around the world, are still trying to sort it out.

The mantra, as with the Holocaust and other horrific events, is “Never forget,” a proper and worthy sentiment, something to strive for. Sadly, it is easy to forget something you did not live through. Twenty years later, I watch the young people drinking and eating at the outdoor dining platforms built during this pandemic. They are rattling on in loud, drunken voices about their weekends, their jobs, their relationship grievances. They may not remember when the planes struck. A child’s memory is not the same as the memory of an adult. They were children when this happened.

I have an early memory of ripping apart a wooden bird toy that hung above my crib. My first big memory, though, is of JFK’s funeral. I was three and lying on the floor, pillow behind my head, watching the sad procession on a nineteen-inch black and white TV. My mom was nearby, grimmer than I had ever seen her. More than anything, I remember the riderless horse in the procession, empty boots backwards in the stirrups. That is my memory. My brother was 12 at the time and his memory is very different. And the adults? They remember it all from a different perspective, commentary and all, brushed over with their own emotions.

The only way to ultimately “never forget” is to educate yourself and educate others. Write a book, tell stories, devote your life to it. Memory, like anything else, must become an action. It’s not some passive thing that we just experience. Just as faith is an action in many ways, to paraphrase some book I once read, memory without works is dead.

I was going to write this article yesterday, but I was tired and distracted. I didn’t want to do it. Today, I woke up and still didn’t want to do it, but I hope to put it behind me by writing this. Not to forget, but to put it in its place, its proper memory hole.

I have not wanted to visit Ground Zero, the museum or any of it. I used to know people there. I delivered pastry to Windows on the World and knew the whole kitchen staff there in the early 90s, along with people from Marsh & McLennan and Cantor Fitzgerald. I knew the elevator operators and the security guys. They would let me park my truck in front of Tower 1, even though I wasn’t supposed to. I remember driving to the Trade Center in 1993 and having to turn back because the freight garage I used had been bombed. I knew the guys down there, as well.

I have had no desire to return, but I had a plan. I figured that I would one day move away from Manhattan, something that may still happen. My plan was to have everything in place and, the day before I left, I would go down to the memorial and say my goodbyes, then leave town. It seemed like something I had to do.

Just a few weeks ago, I was on my bike and discovered a stretch of Greenwich Street that reopened for the first time in years. I was intrigued, so I rode down it and there, just on the right, was the memorial. I hesitated, then rolled up to the sidewalk and walked to the guardrail, where I looked long and hard at the south tower memorial pool. They did a good job with it. I don’t know why I was surprised at how big that footprint is, but it had gotten smaller in my head over the years. It was the first time in 20 years that I was there, even though I have driven and bicycled past the spot hundreds of times.

I don’t think I could forget any of it if I tried. The ability to forget things is a critical one in life, but I could not, nor do I desire to forget that day or the way I felt. I’m not sure I have the ability to control something that big. Varlam Shalamov, a gulag survivor, famously said, “A human being survives by his ability to forget. Memory is always ready to blot out the bad and retain only the good.”

I guess I agree. I could never disagree with Mr. Shalamov. Mariano Rivera, the great Yankee closer, when asked about coming back from a blown save, said something along the lines of “You have to learn to forget yesterday.” Those were not his exact words, but that’s the gist of it. In order for life to go on, you need to be in the moment and not live in the memories of the past. It’s difficult to do that with something so huge and so awful, though.

For at least 10 years, every time I looked downtown, all I saw was a big hole in the skyline where the towers had been. When the steel went up for the new building, it helped to heal me a bit. There was no longer an empty space to remind me daily of what had been.

Can we replace a terrible memory with something new? No. Does time truly heal all wounds? Maybe. If it does, it’s by allowing life form new layers over the old wound. Sometimes, I think I can only escape the memory with physical distance. That’s probably not true, either. Forgetting is a skill and so is remembering. One day I may know what to remember and what to forget.

All photos by Paul Vlachos.

This piece first appeared in EXIT CULTURE: WORDS AND PHOTOS FROM THE OPEN ROAD. You can purchase the book on Amazon HERE.

You can contribute any amount to Juke using these Venmo and Paypal links:

Paul Vlachos is a writer, photographer and filmmaker. He was born in New York City, where he currently lives. He is the author of “The Space Age Now,” released in 2020, “Breaking Gravity,” in 2021, and “Exit Culture” in 2023.

This piece is one to be encased in history. It tells so much of the intimate story of 911. Bravo, Paul.

Great piece and ace photos!